Paper Content:

Page 1:

Hardware.jl — An MLIR-based Julia HLS Flow (Work in Progress)

Benedict Short

Imperial College London

UKIan McInerney

Imperial College London

UKJohn Wickerson

Imperial College London

UK

ABSTRACT

Co-developing scientific algorithms and hardware accelerators re-

quires domain-specific knowledge and large engineering resources.

This leads to a slow development pace and high project complexity,

which creates a barrier to entry that is too high for the majority

of developers to overcome. We are developing a reusable end-to-

end compiler toolchain for the Julia language entirely built on

permissively-licensed open-source projects. This unifies accelera-

tor and algorithm development by automatically synthesising Julia

source code into high-performance Verilog.

1 INTRODUCTION

Rising throughput and latency demands from scientific algorithms

mean that they can no longer rely on advancements in computer

architecture or fabrication processes for uplifts in performance.

Instead, they must take advantage of changes across the stack by

reallocating silicon budget to custom accelerators in both FPGA and

ASIC designs [ 17]. Resource-constrained environments, such as em-

bedded real-time control systems and signal processing algorithms,

have already adopted this approach to develop next-generation

electric motors and software-defined radios. This, however, comes

at the cost of developing and maintaining two separate implementa-

tions at different layers of abstraction known as the "two-language"

problem [ 3] — algorithms are developed using mathematically-

friendly languages like Julia or Matlab and the accelerators are

specified at the RTL level using Verilog or VHDL. Unifying the

development process with HLS tools results in faster prototyping,

lower development costs and makes this technology accessible to

engineers and researchers beyond the hardware domain.

1.1 Toolchain Objectives

The objectives of our toolchain are outlined below:

•Facilitate quick end-to-end accelerator design

•Be reusable and easy-to-maintain

•Enable direct hardware synthesis from pure Julia source code

•Support common hardware synthesis tools (extensibility)

1.2 Why Julia?

Julia [ 2] is an open-source, high-performance, dynamically typed

language built on top of the LLVM framework [ 15] aiming to solve

the "two-language" problem [ 3]. Its popularity in the scientific

community comes from its intuitive syntax, which closely resembles

mathematical notation. Julia’s extensible compiler infrastructure

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored.

For all other uses, contact the owner/author(s).

LATTE ’25, March 30, 2025, Rotterdam, Netherlands

©2025 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).has promoted the development of cross-compilation frameworks for

accelerators using different programming paradigms, such as GPUs

[1], TPUs [ 11] and GraphCore IPUs [ 12]. Another key advantage is

that the ecosystem mainly supports ‘pure Julia packages’ making it

more efficient to compile entire libraries to different targets, unlike

popular alternatives such as Python.

1.3 What about existing toolchains?

Existing HLS toolchains for high-level languages, such as Mat-

lab [ 19], are proprietary and generate poorly optimised designs

[8], while other HLS tools operate at low levels of abstraction not

used for algorithm development (e.g synthesising C/C++, Domain-

Specific Languages and RTL equivalents) [4, 9, 10, 14, 21].

In 2022, Biggs et al. [ 3] proposed a solution that successfully

compiled control-flow Julia programs into dynamically scheduled

VHDL, but noted that their tool suffered from a lack of hardware-

specific compiler optimisations and that future work would require

more program information to be extracted to support memory and

vector operations. Our work now solves this by implementing an

MLIR-based workflow to leverage reusable compiler infrastructure

and more powerful intermediate representations.

At JuliaCon 2024, Lounes posited the possibility of using Julia as

an MLIR front end to integrate with existing statically scheduled

HLS infrastructure [ 18], but we take this idea a step further and im-

plement a fully reusable HLS pipeline native to Julia that leverages

both static and dynamic scheduling.

2 MLIR-BASED FLOW

We use MLIR [ 16] to address fragmented HLS pipelines and reduce

the cost of developing a new domain-specific compiler by reusing

established dialects and interfaces. Standardised infrastructure also

makes our solution easy to maintain and allows for innovation at

higher levels of abstraction to avoid ‘reinventing the wheel’.

2.1 Extracting MLIR

Julia’s nominative, dynamic and parametric type system enables

quick prototyping and language-level polymorphism, but the in-

flexibility of statically compiled accelerators presents an inherent

challenge for this project. Standard MLIR dialects allow us to offload

this challenge to the front end and enforce type-stable IR code to

avoid exponentially increasing the overall design size. Lattner et

al. also describe premature lowering as "the root of all evil" [ 16],

emphasising the importance of extracting high-level dialects.

2.2 Converting MLIR to Verilog

We leverage the open-source CIRCT [ 7] framework to deterministi-

cally generate syntactically correct Verilog and keep our end-to-end

compilation stack within the MLIR ecosystem. CIRCT directly ac-

cepts a selection of standard MLIR dialects and provides a library ofarXiv:2503.09463v1 [cs.SE] 12 Mar 2025

Page 2:

LATTE ’25, March 30, 2025, Rotterdam, Netherlands Benedict Short, Ian McInerney, and John Wickerson

hardware-specific dialects and passes, allowing us to develop a fully

customisable HLS back end that not only supports both dynamic

and static scheduling, but also targets a wide range of existing

synthesis tools. We also considered using other MLIR-based back

ends such as Dynamatic [ 14] and ScaleHLS [ 21], but they are too

restrictive to be used in a stand-alone fashion as they only support

either dynamic or static scheduling respectively. Instead, they could

be integrated as part of a larger back end that combines these tools

in a hybrid manner, similar to the Dynamic and Static Scheduling

(DASS) toolchain proposed by Cheng et al. [5].

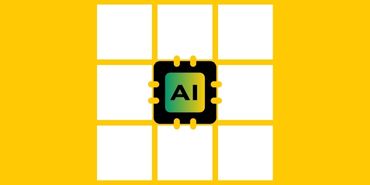

3 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE

The toolchain architecture is inspired by the Bambu HLS frame-

work [ 10]. It is split into three separate components to promote

maintainability and modularity, as shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1: Tool Architecture

3.1 Front End

Our front end differs from other tools by mapping Julia constructs

to hardware-friendly MLIR instead of focussing entirely on high-

level concepts. The Core.Compiler package allows us to create

anAbstractInterpreter that uses a custom inlining policy and

then lowers source-code into type-stable Julia SSA-form IR. The

AbstractInterpreter also allows us to implement method table

overlays to integrate directly with Julia’s JIT interpreter and sup-

port the notion of ‘world age’. We take advantage of Julia’s built-in

type inference to support compile-time polymorphism and reuse

standard high-level optimisations, such as converting dynamic dis-

patch into static dispatch. In the majority of cases, this approach

enables a one-to-one mapping between the Julia typed IR and its

standard MLIR equivalent, similar to the Brutus.jl project [ 6].

The custom inlining policy allows us to overcome the inherent lack

ofcall andinvoke to generate MLIR that is suitable for hardware

synthesis. The end of the pipeline applies lifting passes to raise

source code to higher levels of abstraction.

3.2 Back End

Currently, the back end supports both static and dynamic schedul-

ing by incrementally lowering standard MLIR to the handshake and

calyx dialects. This is then further lowered to the SystemVerilog

dialects and used to generate synthesisable Verilog. The current

architecture and lowering routes are inspired by the HLS tool pro-

vided with the CIRCT library. Communication with the back end is

implemented using a standardised interface, making it a seamless

process to integrate additional back ends into our toolchain.

4 THE ROADMAP

This project is currently under continuous development and will be

made open-source with permissive licensing. The planned future

steps are as follows.4.1 Front End

The first aim will be to incorporate a larger subset of the Julia lan-

guage to synthesise a wide range of existing Julia packages and

libraries. We will also create a custom dialect to avoid a monolithic

architecture and produce a standard interface for complex language

constructs, such as arrays, that cannot be trivially mapped to their

MLIR equivalents. The end goal is to take advantage of statically

known program information to make unsupported constructs syn-

thesisable, for example, exploiting knowledge that dynamic arrays

will never be larger than a given size to convert them into static

arrays. Another aim is to raise Julia directly to Polyhedral MLIR

to avoid premature lowering and allow for greater optimisation

opportunities, similar to the Polygeist project for C/C++ [20].

4.2 Back End

We will write a wrapper for the CIRCT library to bring the en-

tire HLS back end to Julia. This will provide a platform for HLS

research that will allow tools to be prototyped without needing

to build LLVM, CIRCT or C++ projects and consequently speed

up development time. In future, this could be extended further by

implementing advanced identification of static and dynamic islands

[5] to produce highly optimised HLS designs.

4.3 Evaluation

The compiler toolchain will be evaluated against a set of standard

benchmarks to determine performance and design correctness, sim-

ilar to existing Julia GPU compilation frameworks. The benchmarks

shipped with Julia are very limited, and so a wide range of test pro-

grams need to be written to provide a quantitative evaluation of the

performance of this compiler stack. The tool will also be evaluated

against the high-level ideology to ensure that it is user-friendly and

integrates well into the existing Julia ecosystem.

4.4 Testing the compilation stack

First, we plan to take advantage of CIRCT’s formal verification

tooling and built-in logical equivalence checker to verify the cor-

rectness of the lowering passes. Concerns have been raised about

the reliability of HLS toolchains [ 13] and we will overcome this by

using a simple Julia fuzzer to automatically generate synthesisable

designs and check for equivalence.

5 LONG-TERM VISION

The AMD Vitis HLS tool supports source-level testbench cosimula-

tion to test the correctness of generated designs against a golden

model. Integrating this into the Hardware.jl compiler toolchain

would significantly increase the implicit trust that end-users have in

the tool. The ESIdialect within CIRCT provides the cosim endpoint,

which could be used as a starting point for this work.

Alternative use cases of CIRCT’s formal verification framework

would be greatly beneficial to this project and would allow the

HLS developers to provide guarantees on design correctness or

performance. This would also be entirely reusable across all CIRCT

projects.

Page 3:

Hardware.jl — An MLIR-based Julia HLS Flow (Work in Progress) LATTE ’25, March 30, 2025, Rotterdam, Netherlands

REFERENCES

[1]Tim Besard, Christophe Foket, and Bjorn De Sutter. 2019. Effective Extensible

Programming: Unleashing Julia on GPUs. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and

Distributed Systems 30, 4 (2019), 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2018.

2872064

[2]Jeff Bezanson, Alan Edelman, Stefan Karpinski, and Viral B Shah. 2017. Julia:

A fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM Review 59, 1 (2017), 65–98.

https://doi.org/10.1137/141000671

[3]Benjamin Biggs, Ian McInerney, Eric C. Kerrigan, and George A. Constantinides.

2022. High-level Synthesis using the Julia Language. In Proceedings of the 2nd

Workshop on Languages, Tools, and Techniques for Accelerator Design (LATTE’22)

(Lausanne, Switzerland). arXiv:2201.11522 https://capra.cs.cornell.edu/latte22/

paper/7.pdf

[4]Andrew Canis, Jongsok Choi, Mark Aldham, Victor Zhang, Ahmed Kammoona,

Tomasz Czajkowski, Stephen D. Brown, and Jason H. Anderson. 2013. LegUp:

An open-source high-level synthesis tool for FPGA-based processor/accelerator

systems. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 13, 2, Article 24 (Sept. 2013), 27 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2514740

[5]Jianyi Cheng, Lana Josipović, George A. Constantinides, Paolo Ienne, and John

Wickerson. 2022. DASS: Combining Dynamic and Static Scheduling in High-Level

Synthesis. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and

Systems 41, 3 (2022), 628–641. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAD.2021.3065902

[6]Valentin Churavy, Leon Shen, McCoy R. Becker, and Stephen Neuendorffer. 2020.

Brutus.jl. https://github.com/JuliaLabs/brutus Accessed: January 28, 2025.

[7]CIRCT Contributors. 2020. CIRCT. https://github.com/llvm/circt Accessed:

January 28, 2025.

[8]Serena Curzel, Michele Fiorito, Patricia Lopez Cueva, Tiago Jorge, Thanassis

Tsiodras, and Fabrizio Ferrandi. 2023. Exploration of Synthesis Methods from

Simulink Models to FPGA for Aerospace Applications. In Proceedings of the 20th

ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers (Bologna, Italy) (CF ’23) .

Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 243–249. https:

//doi.org/10.1145/3587135.3592766

[9]John Demme and Aaron Landy. 2022. Using CIRCT for FPGA Physical Design.

InProceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Languages, Tools, and Techniques for Accel-

erator Design (LATTE’22) (Lausanne, Switzerland). https://capra.cs.cornell.edu/

latte22/paper/10.pdf Accessed 28 January 2025.

[10] Fabrizio Ferrandi, Vito Giovanni Castellana, Serena Curzel, Pietro Fezzardi,

Michele Fiorito, Marco Lattuada, Marco Minutoli, Christian Pilato, and An-

tonino Tumeo. 2021. Invited: Bambu: an Open-Source Research Framework

for the High-Level Synthesis of Complex Applications. In 2021 58th ACM/IEEE

Design Automation Conference (DAC) (San Francisco, CA, USA). IEEE, 1327–1330.

https://doi.org/10.1109/DAC18074.2021.9586110

[11] Keno Fischer and Elliot Saba. 2018. Automatic Full Compilation of Julia Programs

and ML Models to Cloud TPUs. arXiv:1810.09868 [cs.PL] https://arxiv.org/abs/

1810.09868

[12] Mosè Giordano. 2023. Heterogeneous computing with the Julia language:

from A64FX to the IPU. Barcelona Supercomputing Center Research Semi-

nar. https://www.bsc.es/research-and-development/research-seminars/sors-

heterogeneous-computing-the-julia-language-a64fx-the-ipu Accessed 28 Janu-

ary 2025.

[13] Yann Herklotz, Zewei Du, Nadesh Ramanathan, and John Wickerson. 2021. An

empirical study of the reliability of high-level synthesis tools. In 2021 IEEE

29th Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing

Machines (FCCM) (Orlando, FL, USA). IEEE, 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1109/

FCCM51124.2021.00034

[14] Lana Josipović, Andrea Guerrieri, and Paolo Ienne. 2020. Invited Tutorial: Dy-

namatic: From C/C++ to Dynamically Scheduled Circuits. In Proceedings of the

2020 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays

(Seaside, CA, USA) (FPGA ’20) . Association for Computing Machinery, New York,

NY, USA, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373087.3375391

[15] Chris Lattner and Vikram Adve. 2004. LLVM: A compilation framework for

lifelong program analysis & transformation. In International symposium on code

generation and optimization, 2004. CGO 2004. (San Jose, CA, USA). IEEE, 75–86.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CGO.2004.1281665

[16] Chris Lattner, Mehdi Amini, Uday Bondhugula, Albert Cohen, Andy Davis,

Jacques Arnaud Pienaar, River Riddle, Tatiana Shpeisman, Nicolas Vasilache,

and Oleksandr Zinenko. 2021. MLIR: Scaling Compiler Infrastructure for Do-

main Specific Computation. In 2021 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on

Code Generation and Optimization (CGO) (Seoul, Korea (South)). IEEE. https:

//doi.org/10.1109/CGO51591.2021.9370308

[17] Charles E. Leiserson, Neil C. Thompson, Joel S. Emer, Bradley C. Kuszmaul,

Butler W. Lampson, Daniel Sanchez, and Tao B. Schardl. 2020. There’s plenty

of room at the Top: What will drive computer performance after Moore’s law?

Science 368, 6495 (2020), eaam9744. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam9744

[18] Gaëtan LOUNES. 2024. Julia meets Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA).

https://pretalx.com/juliacon2024/talk/RJEPZY/. Accessed: 2025-01-25.[19] MathWorks. 2024. High-Level Synthesis. Online. https://uk.mathworks.com/

discovery/high-level-synthesis.html Accessed: 2024-01-28.

[20] William S. Moses, Lorenzo Chelini, Ruizhe Zhao, and Oleksandr Zinenko. 2021.

Polygeist: Raising C to Polyhedral MLIR. In 2021 30th International Conference

on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques (PACT) (Atlanta, GA, USA).

IEEE, 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1109/PACT52795.2021.00011

[21] Hanchen Ye, Cong Hao, Jianyi Cheng, Hyunmin Jeong, Jack Huang, Stephen

Neuendorffer, and Deming Chen. 2022. ScaleHLS: A New Scalable High-Level

Synthesis Framework on Multi-Level Intermediate Representation. In 2022 IEEE

International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA)

(Seoul, Korea, Republic of). IEEE, 741–755. https://doi.org/10.1109/HPCA53966.

2022.00060