Authors: Huatong Song, Jinhao Jiang, Yingqian Min, Jie Chen, Zhipeng Chen, Wayne Xin Zhao, Lei Fang, Ji-Rong Wen

Paper Content:

Page 1:

R1-Searcher: Incentivizing the Search Capability in

LLMs via Reinforcement Learning

Huatong Song1∗, Jinhao Jiang1∗, Yingqian Min1, Jie Chen1, Zhipeng Chen1,

Wayne Xin Zhao1†, Lei Fang2, Ji-Rong Wen1

1Gaoling School of Artificial Intelligence, Renmin University of China.

2DataCanvas Alaya NeW

{songhuatong123, jiangjinhao}@ruc.edu.cn

batmanfly@gmail.com

Abstract

Existing Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) have shown the potential of reinforce-

ment learning (RL) to enhance the complex reasoning capabilities of Large Lan-

guage Models (LLMs). While they achieve remarkable performance on challenging

tasks such as mathematics and coding, they often rely on their internal knowledge

to solve problems, which can be inadequate for time-sensitive or knowledge-

intensive questions, leading to inaccuracies and hallucinations. To address this,

we propose R1-Searcher , a novel two-stage outcome-based RL approach de-

signed to enhance the search capabilities of LLMs. This method allows LLMs

to autonomously invoke external search systems to access additional knowledge

during the reasoning process. Our framework relies exclusively on RL, without

requiring process rewards or distillation for a cold start. Our experiments demon-

strate that our method significantly outperforms previous strong RAG methods,

even when compared to the closed-source GPT-4o-mini. The code is available at

https://github.com/SsmallSong/R1-Searcher .

1 Introduction

Large Reasoning Models (LRMs), such as OpenAI-o1 [ 1], Deepseek-R1 [ 2] and Kimi-k1.5 [ 3],

have demonstrated the significant impact of reinforcement learning (RL) in enhancing the reasoning

capabilities of large language models (LLMs) [ 4]. However, since they primarily rely on their

internal knowledge, these models may struggle with open-ended tasks, particularly those involving

knowledge-intensive questions [ 5,6], private information in local databases [ 7,8], and time-sensitive

issues [ 9,10]. This reliance may easily lead to inaccuracies and hallucinations. Therefore, it is

crucial to enable LLMs to access external information during the reasoning process to achieve more

deliberative reasoning [11].

To address this issue, extensive research has focused on augmenting LLMs with external information

sources ( a.k.a., retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [ 12,13]). Early approaches emphasize specific

prompting strategies to guide LLMs in iterative question decomposition, query generation, and

sub-question answering [ 14,15,16]. While effective, these complex prompt designs may rely on

closed-source LLMs for achieving optimal performance. Subsequent studies investigate to distill this

capability into smaller LLMs through supervised fine-tuning (SFT) [ 17]. However, recent findings

suggest that SFT-based distillation can cause models to memorize solution paths, limiting their

generalization to novel scenarios [ 18]. Recent proposals include a test-time scaling method [ 11,19],

notably employing the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) framework to enhance solution-finding by

expanding the search space during inference. Despite its promise, this approach incurs significant

∗Equal contribution.

†Correspondence to Wayne Xin Zhao.

Preprint. Under review.arXiv:2503.05592v1 [cs.AI] 7 Mar 2025

Page 2:

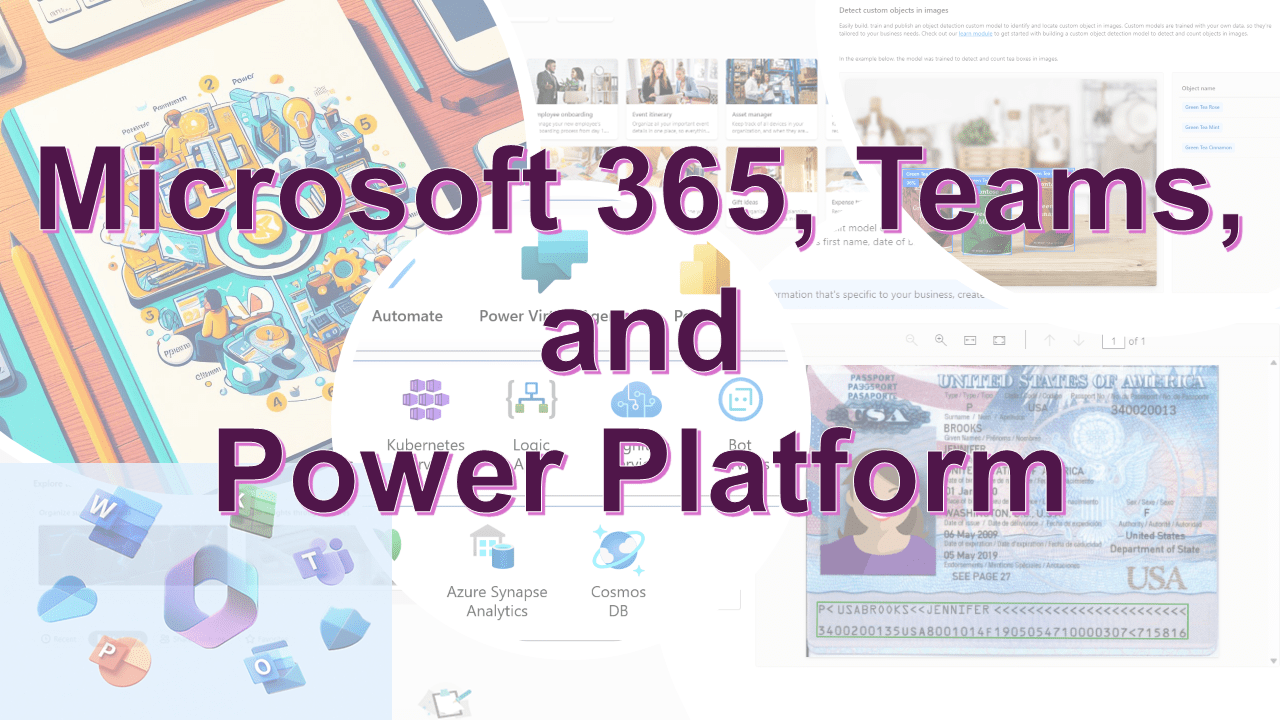

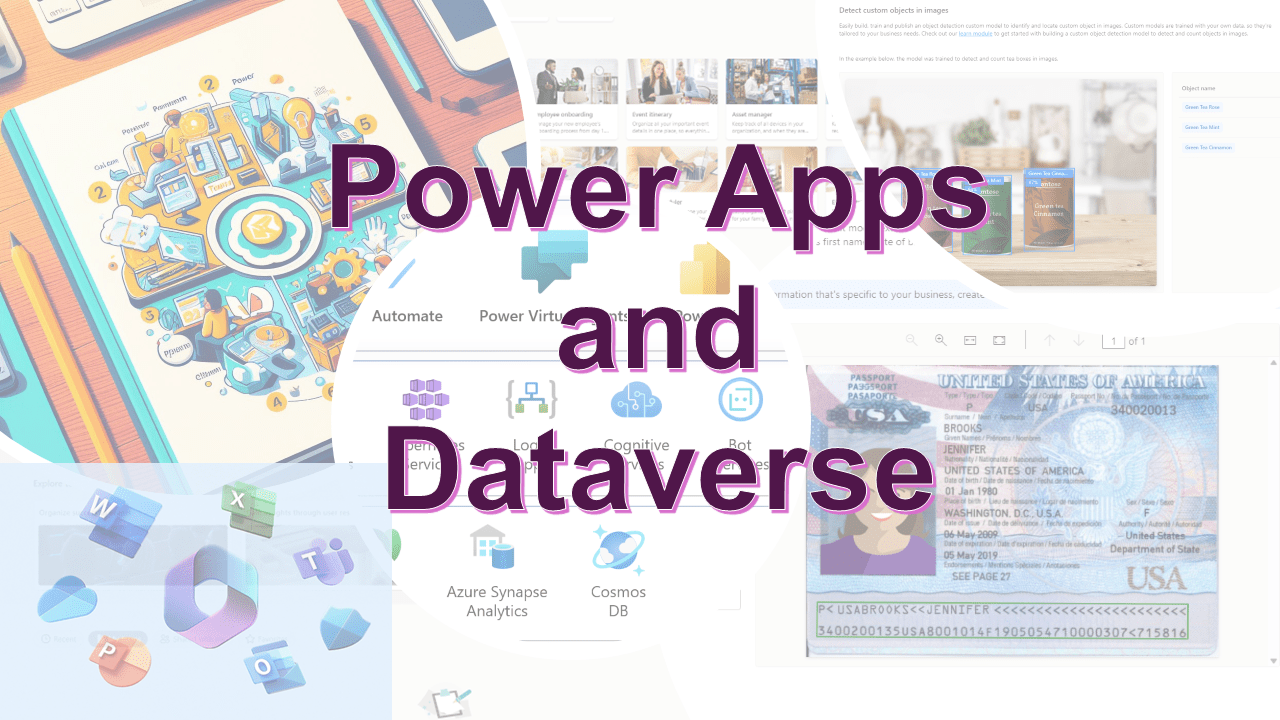

HotpotQA 2WikiMultiHopQA Bamboogle Musique01020304050607080Accuracy / Percentile (%)75.074.6

50.6

41.6

30.834.865.0

62.8

53.4

47.8

11.418.454.454.454.4

52.4

18.420.031.4

28.230.2

26.2

21.4

10.4Qwen2.5-7B-RL (Ours)

Llama-3.1-8B-RL (Ours)

ReART eR (GPT-4o-mini)

CR-Planer (GPT-4o-mini)

IRCoT (GPT-4o-mini)

Marco-o1 (GPT-4o-mini)Figure 1: Performance comparisons between R1-Searcher and other methods on four multi-hop QA

benchmarks. R1-Searcher achieves state-of-the-art performance on each dataset.

inference overhead, reducing its practicality for widespread use. Therefore, we propose integrating

an external retrieval environment during training, enabling models to explore and learn to effectively

utilize retrieval for problem-solving. This approach aims to incentivize the search capability in LLMs,

thereby enhancing LLMs’ generalization and improving inference efficiency.

In this paper, we introduce R1-Searcher , a novel framework to enhance the RAG capabilities of

LLMs with RL. Our core motivation is to incentivizing the search capability in LLMs via exploring

with an external retrieval environment. To implement it, we design a two-stage, outcome-based RL

approach, enabling the model to freely explore how to invoke an external retrieval system to acquire

relevant knowledge during the reasoning process through a tailored reward design. Specifically, in

the first stage, we employ the retrieve-reward to incentivize the model to conduct retrieval operations

without considering the final answer accuracy. In this way, the LLMs can quickly learn the correctly

retrieval invocation format. In the second stage, we further introduce the answer reward to encourage

the model to learn to effectively utilize the external retrieval system to solve question correctly.

Our method relies solely on outcome-based RL, allowing the model to learn autonomously through

exploration and learning without requiring any distillation or cold start with SFT. To support the

exploration between LLMs and the external retrieval environment during the training process, we

further propose a modified RL training method based on Reinforce++ [ 20] with RAG-based rollout

and retrieval mask-based loss calculation.

We conduct extensive experiments to verify the effectiveness of our method using various LLM

backbones on four representative benchmarks, based on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Qwen-2.5-7B-

Base. Notably, our method surpasses the strong baseline with GPT-4o-mini ( i.e.,ReARTeR) by up to

48.22% on HotpotQA and 21.72% on 2Wiki when using Qwen-2.5-7B-Base. To access generalization

capability, we evaluate our method on the Bamboogle dataset using an online search, which is not seen

during training. Our model achieved an 11.4% performance improvement on Bamboogle compared

to the Search-o1 with 32B parameters.

Our principal contributions are as follows:

•We introduce R1-Searcher, which utilizes a two-stage RL framework to enable autonomous retrieval

during the reasoning process.

•Extensive experiments on four multi-hop datasets show that R1-Searcher consistently and signifi-

cantly surpasses existing RAG methods, even close-sourced GPT-4o-mini.

2

Page 3:

•Our approach exclusively employs RL for training without any distillation or cold start, while

showing great generalization to out-of-domain datasets and online search scenarios. It is effective for

both base and instruction-tuned models.

2 Method

2.1 Data Selection

In this study, we aim to enhance the search capabilities of LLMs for problem-solving within a

retrieval environment using an outcome-based RL method. However, the independence of the

retrieval environment may lead to issues that exceed its query scope during the RL training process,

posing challenges to successful problem resolution and affecting the training efficiency. To address

this, we conduct data selection and incorporate questions with varying difficulty levels.

Specifically, we select training data from the training sets of two representative multi-hop question

answering datasets, namely HotpotQA [ 5] and 2WikiMultiHopQA [ 6]. We utilize the Qwen-2.5-7B-

Instruct [ 21] model, equipped with a local retrieval system, and prompt the model (Prompt 2.1) in

solving questions from these datasets using the external retrieval system. The prompt is provided

below. Based on the number of rollouts required to correctly answer a question, we categorize the

data into three levels of difficulty: easy (fewer than 10 rollouts), medium (10 to 20 rollouts), and

difficult (more than 20 rollouts). These difficulty levels are then combined as delineated in Table 1 to

construct our training dataset.

Stage Dataset Easy Medium Difficult

Stage-1HotpotQA - 200 -

2WikiMultiHopQA - 150 -

Stage-2HotpotQA - 2561 2000

2WikiMultiHopQA - 1087 2500

Table 1: The information of the data used during RL training.

System Prompt for Data Selection

You are a helpful assistant. Given a question, you should answer it by first thinking about the reasoning

process in the mind and then providing the final answer. The output format of reasoning process and final

answer are enclosed within <think> </think> and <answer> </answer> tags, respectively, i.e., "<think>

reasoning process here </think><answer> final answer here </answer>". You should perform thinking

with decomposing, reflecting, brainstorming, verifying, refining, and revising. Besides, you can perform

searching for uncertain knowledge if necessary with the format of "<|begin_of_query|> search query

(only keywords) here <|end_of_query|>".""" Then, the search system will provide you with the retrieval

information with the format of "<|begin_of_documents|> ...search results... <|end_of_documents|>".

2.2 Two-Stage Outcome-based Reinforcement Learning

To progressively improve the search capabilities of LLMs, we propose a two-stage outcome-based

RL training method. In Stage-1, the model is trained to effectively utilize an external retrieval system.

In Stage-2, the model is trained to incorporate search during the reasoning process to accurately solve

questions.

2.2.1 Reward Design

Due to the absence of intermediate annotations in the training data, the RL process is primarily influ-

enced by outcome rewards. By assigning distinct rewards across two stages, the model progressively

learns to invoke the external retrieval system and effectively integrate retrieved documents into the

reasoning process to answer questions.

In Stage-1, the reward function comprises a retrieval reward and a format reward. The primary goal

here is to enable the model to recognize its ability to invoke the external retrieval system and learn

its utilization, without considering the correctness of the model’s answers. The model is explicitly

3

Page 4:

encouraged to initiate search queries, and thus, no answer reward is assigned at this stage. Specifically,

the retrieval reward is defined as follows:

Rretrieval =�0.5, n≥1

0, n = 0(1)

where nrepresents the number of retrieval invocations. For the format reward, we first define the

correct format as follows:

1.The model’s thinking process and final answer should be enclosed within the

<think>...</think> and<answer>...</answer> tags, respectively. Additionally, only

the final short answer is permitted within the <answer>...</answer> tag.

2. The generated output must be free of any garbled or unreadable content.

3.When invoking retrieval, the model should propose a query and encapsulate the query within

the<begin_of_query>...</end_of_query> tags. Furthermore, the model is unable to

generate documents directly without invoking retrieval.

Based on the above format requirements, the format reward is defined as follows:

Rformat =�0.5,if the format is correct

0, if the format is incorrect(2)

Therefore, the final reward of Stage-1 is the sum of the retrieval reward and format reward.

In Stage-2, we eliminate the retrieval reward and incorporate the answer reward. We apply the same

format judgment criteria as in Stage-1, but with different penalties:

R′

format =�0,if the format is correct

-2,if the format is incorrect(3)

For the answer reward, we utilize the F1 score of the ground-truth answer and predicted answer,

which is calculated as follows:

Precision =PN

IN,Recall =RN

IN(4)

F1 =2×Precision ×Recall

Precision +Recall(5)

where PNrepresents the word count of the predicted answer, RNdenotes the word count of the

reference answer, and INindicates the word count of the intersection between the two answers.

Therefore, the final reward of Stage-2 is the sum of the answer reward and the format reward.

2.2.2 Training Algorithm

Our training algorithm is based on the Reinforce++ algorithm, which we have modified to suit our

retrieval-augmented generation scenario. During the reasoning process, the model engages an external

retrieval system to solve problems, receiving a reward for correct solutions. We enhance the model’s

ability to utilize retrieval during the reasoning process by maximizing this reward. Our goal is to

enable the model to autonomously access external knowledge when faced with uncertainty, effectively

integrating reasoning and retrieval. To incorporate retrieved documents seamlessly and ensure rational

model optimization, we implement two modifications to the original algorithm: RAG-based Rollout

andRetrieval Mask-based Loss Calculation .

RAG-based Rollout. As demonstrated in Prompt 2.2.2, we guide the model to

utilize the external retrieval system during the generation process by employing the

tags <begin_of_query>...<end_of_query> to indicate the invocation of the search

tool. Upon generating <end_of_query> , the process pauses, allowing the extraction

and use of the query for retrieval. The retrieved documents are encapsulated within

<begin_of_documents>...<end_of_documents> tags and integrated into the model’s reasoning.

This method ensures that retrieval is seamlessly incorporated into the reasoning process, allowing the

model to continue its reasoning based on the retrieved documents without disruption.

4

Page 5:

System Prompt for Base Model

The User asks a question, and the Assistant solves it. The Assistant first thinks about the reasoning

process in the mind and then provides the User with the final answer. The output format of reasoning

process and final answer are enclosed within <think> </think> and <answer> </answer> tags, respec-

tively, i.e., "<think> reasoning process here </think><answer> final answer here </answer>". During the

thinking process, **the Assistant can perform searching** for uncertain knowledge if necessary with

the format of "<|begin_of_query|> search query (only list keywords, such as "keyword_1 keyword_2

...")<|end_of_query|>". **A query must involve only a single triple**. Then, the search system will

provide the Assistant with the retrieval information with the format of "<|begin_of_documents|> ...search

results... <|end_of_documents|>".

Retrieve Mask-based Loss Calculation. During the training process, the aforementioned solutions

are employed to compute the RL loss, involving the reward, KL divergence, and advantages. When the

model performs retrieval, the retrieved documents are integrated into the reasoning process, serving

as environment observations. The model is not intended to generate these documents. To mitigate the

environmental effect, we designate <begin_of_documents>...<end_of_documents> as special

tokens and mask them during training. This prevents these external tokens from influencing the

loss calculation, ensuring that the retrieved documents do not interfere with the model’s intrinsic

reasoning and generation processes.

3 Experiment

3.1 Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

In training the R1-Searcher, we perform data selection from the training sets of HotpotQA and

2WikiMultiHopQA (see 1). We evaluate using four multi-hop datasets: HotpotQA [ 5], 2WikiMulti-

HopQA [ 6], Musique [ 22], and Bamboogle [ 9]. HotpotQA and 2WikiMultiHopQA are in-domain

benchmarks since parts of their training sets are used for reinforcement learning. In contrast, Musique

and Bamboogle serve as out-of-domain benchmarks to assess our model’s generalization capabilities.

For evaluation metrics, following existing work [ 23], we utilize Cover Exact Match (ACC_R) and

LLM-as-Judge (ACC_L), given the nature of open-ended multi-hop questions. Cover Exact Match

assesses whether the ground truth answer is included in the predicted answer, while LLM-as-Judge

uses GPT-4o-mini to evaluate the correctness of the predictions. The evaluation prompt for ACC_L

is as follows:

Judge Prompt

Given a Question and its Golden Answer, verify whether the Predicted Answer is correct. The prediction

is correct if it fully aligns with the meaning and key information of the Golden Answer. Respond with

True if the prediction is correct and False otherwise.

Question:

Golden Answer:

Predicted Answer:

3.2 Baselines

We utilize Qwen-2.5-7B-Base and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct as the backbone models for our training.

We compare R1-Searcher against the following baselines, based on GPT-4o-mini and Llama-3.1-8B-

Instruct:

•Naive Generation: Direct generation of answers without retrieval.

•Standard RAG: Traditional retrieval-augmented generation systems.

•Branching Methods (Branching): SuRe [ 24] and REPLUG [ 25], which execute multiple reasoning

paths in parallel for a single query.

•Summarization-based Methods (Summary): LongLLMLingua [ 26], RECOMP [ 27], and

Selective-Context [28], which employ compressors to summarize retrieved documents.

5

Page 6:

•Adaptive Retrieval Methods (AR): SKR [ 29], which adaptively retrieves based on the generator’s

knowledge.

•RAG-CoT Methods (RAG-CoT): Self-Ask [ 30], Iter-RetGen [ 31], and IRCoT [ 32], integrating

retrieval-augmented generation with chain-of-thought reasoning.

•Test-time Scaling Methods (Test-Time): CR-Planner [ 19], ReARTeR [ 23], which scale retrieval-

augmented generation at test time using Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS).

•Reasoning Models (Reasoning): Marco-o1-Qwen-7B [ 33] and Skywork-o1-Llama-3.1-8B [ 34],

employing standard retrieval-augmented generation.

3.3 Implementation Details

All baseline models adhere to the ReARTeR framework and are evaluated using FlashRAG [ 35]. The

retrieval corpus comprises the English Wikipedia as provided by KILT [ 36] in 2019, segmented into

100-word passages with appended titles, totaling 29 million passages. We employ BGE-large-en-v1.5

as the text retriever. Given the timeliness of knowledge in Bamboogle, we utilize the Google Web

Search API for online webpage search tests to further evaluate our model’s generalization capabilities

to online search (Section 4.4).

For our R1-Searcher, the backbone model incorporates Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct or Qwen-2.5-7B-Base.

The training data of the Stage-1 includes 200 medium samples from the HotpotQA training set and

150 medium samples from the 2WikiMultiHopQA training set. And the training data of Stage-2

consists of 4561 samples from HotpotQA, with 2561 medium and 2000 hard samples (Table 1), and

3581 samples from 2WikiMultiHopQA, also with 1087 medium and 2500 hard samples. Each data

sample undergoes 16 rollouts during training, with a train batch size of 256 and a rollout batch size

of 64. The learning rate is 2e-6. We utilize DeepSpeed’s Zero-2 [ 37], with a sampling temperature of

1.0 and a maximum retrieval count of 8. The training epoch is set to 1, with KL divergence set to 0

for Qwen-2.5-7B-Base and 1e-4 for Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. The discount factor γis set to 1 in the

cumulative discounted reward calculation.

3.4 Main Results

Table2 shows the results of R1-Searcher and the baselines on four mutil-step benchmarks. We can

obtain the following observations:

•Achieving Significant Performance Improvement on Multi-Hop QA. ReARTeR demonstrates superior

performance among existing baselines, highlighting the advantages of the test-time scaling method.

However, it relies on MCTS for solution exploration, which incurs significant overhead due to

increased retrieval invocations. In contrast, our proposed R1-Searcher, utilizing the same LLaMA-

3.1-8B-Instruct backbone model, achieves notable performance enhancements over ReARTeR and

other baselines. Specifically, our method yields improvements of 48.2% on HotpotQA, 21.7% on

2WikiMultiHopQA, and 4.0% on Bamboogle according to the LLM-as-Judge metric. This indicates

that our method can efficiently facilitates the model to conduct accurate retrieval invocations during

the reasoning process.

•Supporting RL Learning from Base LLM without Cold Start. Furthermore, we also conduct RL

learning from scratch using a powerful base model, such as Qwen-2.5-7B-Base. Surprisingly, we

can achieve better results and obtain the best performance on most in-domain and out-of-domain

datasets, even surpassing the closed-source LLM such as GPT-4o-mini. These results demonstrate

the effectiveness of our two-stage RL method in guiding the LLMs’ learning process.

•Maintaining Generalization Ability. We employ only 8148 samples from the training sets of

HotpotQA and 2WikiMultiHopQA for RL training. The model not only excels on these in-domain

datasets but also demonstrates strong generalization by performing well on the out-of-domain

datasets, such as Musique and Bamboogle. This suggests that the model effectively learns retrieval

and integrates it with reasoning through exploration during RL training, enabling robust performance

on new test datasets requiring retrieval. Furthermore, it can also seamlessly generalizes to online

search, as detailed in Section 4.4.

6

Page 7:

Models Types MethodsHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle Musique

ACC RACC LACC RACC LACC RACC LACC RACC L

GPTZero-ShotNaive Generation 0.324 0.404 0.348 0.346 0.240 0.280 0.134 0.170

Standard RAG 0.342 0.450 0.344 0.292 0.272 0.328 0.172 0.188

BranchingSuRe 0.270 0.380 0.244 0.264 0.168 0.208 0.128 0.146

REPLUG 0.350 0.428 0.296 0.254 0.224 0.256 0.132 0.138

SummaryLongLLMLingua 0.358 0.450 0.324 0.316 0.248 0.288 0.150 0.172

RECOMP 0.332 0.398 0.298 0.306 0.136 0.176 0.118 0.134

Selective-Context 0.366 0.442 0.350 0.290 0.240 0.288 0.152 0.172

Adaptive SKR 0.360 0.454 0.364 0.314 0.248 0.288 0.162 0.174

RAG-CoTSelf-Ask 0.392 0.462 0.336 0.478 0.336 0.416 0.260 0.270

Iter-RetGen 0.374 0.456 0.326 0.270 0.232 0.256 0.178 0.188

IRCoT 0.434 0.308 0.492 0.114 0.272 0.184 0.192 0.214

Test-TimeCR-Planner 0.404 0.416 0.520 0.478 0.488 0.524 0.272 0.262

ReARTeR 0.468 0.506 0.554 0.534 0.496 0.544 0.296 0.302

LlamaZero-ShotNaive Generation 0.208 0.268 0.326 0.254 0.144 0.168 0.068 0.096

Standard RAG 0.334 0.398 0.336 0.212 0.168 0.216 0.104 0.098

BranchingSuRe 0.266 0.346 0.122 0.262 0.160 0.192 0.106 0.144

REPLUG 0.290 0.348 0.334 0.204 0.168 0.232 0.078 0.090

SummaryLongLLMLingua 0.314 0.382 0.304 0.294 0.168 0.216 0.088 0.100

RECOMP 0.318 0.380 0.324 0.322 0.104 0.160 0.112 0.126

Selective-Context 0.296 0.358 0.266 0.204 0.144 0.200 0.092 0.104

Adaptive SKR 0.300 0.372 0.336 0.212 0.176 0.208 0.100 0.112

RAG-CoTSelf-Ask 0.316 0.408 0.306 0.322 0.360 0.432 0.222 0.226

Iter-RetGen 0.302 0.362 0.310 0.224 0.144 0.176 0.084 0.084

IRCoT 0.210 0.146 0.338 0.312 0.120 0.104 0.060 0.042

Test-TimeCR-Planer 0.332 0.350 0.420 0.350 0.304 0.336 0.144 0.098

ReARTeR 0.424 0.434 0.470 0.364 0.438 0.484 0.244 0.252

ReasoningMarco-o1 0.352 0.348 0.442 0.184 0.224 0.200 0.134 0.104

Skywork-o1 0.306 0.256 0.344 0.190 0.176 0.160 0.092 0.060

Llama RLR1-Searcher0.648 0.746 0.594 0.628 0.504 0.544 0.254 0.282

Qwen RL-Zero 0.654 0.750 0.636 0.650 0.528 0.544 0.282 0.314

Table 2: Performance comparisons between R1-Searcher and the baselines on four multi-hop QA

benchmarks. The boldface indicates the best performance. GPT ,Qwen , and Llama are the abbrevia-

tions of GPT-4o-mini, Qwen-2.5-7B-Base, and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, respectively.

4 Further Analysis

In this section, we present a detailed discussion of several key aspects that should be considered

during the training process.

4.1 Basic Training Methods

GRPO or Reinforce++. As two representative RL algorithms that do not require a critic model, we

compare the differences between GRPO [ 38] and Reinforce++ on our RAG tasks. We perform two-

stage training on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, setting the KL divergence to 1e−4and utilizing HotpotQA

and 2Wiki as the training datasets. As shown in Figure 2, although there are no significant differences

in rewards between the two algorithms during training, GRPO demonstrates a clear advantage in both

the length of generated text and the frequency of retrievals. The generation of longer text may widen

the reasoning scope, and the increased frequency of retrievals could potentially improve the accuracy

in responding to queries where the model itself has uncertainty. Moreover, it also demonstrates better

performance on the out-of-domain dataset ( i.e.,Bamboogle), suggesting that GRPO may possess

superior generalization capabilities. However, Reinforce++ exhibits superior performance on the

in-domain test set ( i.e.,HotpotQA and 2Wiki), which seemingly indicates a higher learning efficiency

towards in-domain data.

RL or SFT. In this part, we aim to understand the enhancement effects of SFT and RL through

comparison. We conduct RL training according to the same settings in Section 3.3. For the SFT

7

Page 8:

Figure 2: The log of reward, response length, and retrieval numbers for Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct

comparison between using GRPO and Reinforce++.

MethodHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle

Avg (CEM)

EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1

GRPO 53.0 60.5 68.6 58.0 60.5 63.0 48.0 56.0 60.5 59.0

Reinforce++ 58.4 64.8 70.6 57.5 61.5 62.9 44.0 50.4 57.1 58.9

Table 3: Performance comparison of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct trained using GRPO and Reinforce++ on

three multi-hop QA benchmarks.

data, we select Qwen-2.5-7B-instruct and conduct rollouts from the training sets of HotpotQA and

2Wiki, obtaining 4768 pieces of data with good reasoning paths. Among them, 4268 pieces of data

undergo retrieval, and the training epoch is set to 3. The results are shown in Table 4. We can see

that RL outperforms SFT in both in-domain and out-of-domain test sets, indicating superior retrieval

capability and generalization across varying datasets. After inspecting the outputs of models trained

with both methods (see Section 5.1), we find that although SFT assists the model in generating

retrieval queries, the timing and relevance of these queries are inferior to those produced by RL

training. Specifically, SFT tends to rely on the model’s internal knowledge, which can often be

erroneous or misleading. This indicates that RL may be more effective in enhancing the model’s

retrieval skills.

MethodHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle Avg

(CEM) EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1

Qwen-Base-RL 58.0 65.4 71.9 55.4 63.6 63.7 45.6 52.8 57.7 60.6

Qwen-Base-SFT 37.0 49.5 51.3 42.5 54.5 51.3 40.8 46.4 51.0 50.1

Llama-Instruct-RL 58.4 64.8 70.6 55.0 59.4 61.2 44.0 50.4 57.1 58.2

Llama-Instruct-SFT 36.0 47.0 50.4 38.0 51.0 48.3 39.4 46.6 48.2 48.2

Table 4: Performance comparison of Qwen-2.5-7B-Base and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct trained using RL

and SFT on three multi-hop QA benchmarks. Qwen-Base andLlama-Instruct are the abbreviations

of Qwen-2.5-7B-Base and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, respectively.

4.2 Reward Design

Answer Reward. Here, we investigate the impact of various answer rewards on RL training. We

specifically compare the performance of using Exact Match (EM), Cover Exact Match (CEM), and

F1 score as answer rewards. The F1 score is used directly as its own reward, while the rewards for

EM and CEM are defined as follows:

Ranswer =�1,if EM/CEM is True

-1,if EM/CEM is False(6)

The training log and final results are presented in Figure 3 and Table 5. Firstly, the F1-based answer

reward yields longer response lengths and superior final results compared to CEM and EM-based

8

Page 9:

rewards. Notably, it achieves up to a 52.6% average performance improvement over the EM-based

reward. Secondly, the EM-based reward results in shorter response lengths during training and

poorer performance during testing compared to CEM or F1-based reward. This may be due to EM’s

strictness, making it unsuitable for open-ended question generation scenarios. Overall, F1 provides a

more balanced measure of answer accuracy, serving as a more effective outcome-based reward in this

scenario.

Figure 3: The log of reward, response length, and retrieval numbers for the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model

utilizing different metrics for outcome-supervised reward calculation.

MethodHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle

Avg (CEM)

EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1

EM 55.0 62.0 69.3 29.0 29.0 30.0 24.8 28.0 33.2 39.7

CEM 53.4 65.0 68.8 51.8 59.2 61.7 46.4 54.4 59.0 59.5

F1 58.0 65.4 71.9 55.4 63.6 63.7 45.6 52.8 57.7 60.6

Table 5: Performance comparison of the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model utilizing different metrics for

outcome-supervised reward calculation on three mutil-hop QA benchmarks.

Format Reward. During training, we impose strict constraints on the format reward (see Sec-

tion 2.2.1). These constraints are iteratively refined to address instances of reward hacking and the

generation of unreasonable solutions. The primary issues observed include:

1.The model produces <begin_of_documents>...<end_of_documents> without gener-

ating <begin_of_query>...<end_of_query> , effectively creating “external documents”

independently.

2.When training with the Base model and setting KL to 0, the model occasionally generates

nonsensical output in later training phases, failing to adhere to specified formats.

3.With the Llama model, omitting the Stage-1 training causes the model to bypass retrieval

entirely, directly answering questions without engaging in the retrieval process.

4.Using CEM as the supervisory signal, the model often produces lengthy responses containing

extraneous information, though the correct answer is included.

Through our designed format rewards, we can train the model more stably in the RL training process,

avoiding abnormal outputs and reward hacking.

4.3 Training Data

Difficulty Distribution. In this study, we examine the effect of data difficulty on training by

constructing two distinct datasets. The first dataset, used for primary training, is labeled w. Difficult

(Table 1). The second dataset, w/o Difficult , substitutes questions requiring more than 20 rollouts with

those requiring 10 to 20 rollouts. Both datasets are trained under identical configurations. As shown

9

Page 10:

in Figure 4, training with the w/o Difficult dataset results in shorter generation lengths and fewer

retrievals compared to the w. Difficult dataset. This suggests that more challenging problems prompt

the model to perform additional retrievals to answer questions. Furthermore, Table 6 indicates that

models trained on the w. Difficult dataset achieves superior performance on the evaluation dataset

compared to those trained on the w/o Difficult dataset (achieving 3.4% average CEM performance

improvements on three datasets). This underscores the importance of data difficulty distribution for

model performance in RL, as more challenging questions enhance the model’s reasoning capabilities.

Figure 4: The log of reward, response length, and retrieval numbers for the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model,

trained on datasets of varying difficulty levels.

MethodHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle

Avg (CEM)

EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1

w/o Difficult 54.8 61.8 69.3 55.4 63.6 63.7 44.8 51.2 56.9 58.8

w. Difficult 58.0 65.4 71.9 54.8 64.2 63.8 45.6 52.8 57.7 60.8

Table 6: Performance comparison of the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model trained on datasets of different

difficulty levels on three mutil-hop QA benchmarks.

Data Diversity. We investigate the effect of data diversity during the RL training process. Specifically,

we compare the performance of using a combination of the HotpotQA and 2Wiki datasets, as well as

each dataset individually. The training log and final results are presented in Figure 5 and Table 7,

respectively. We can find that models trained on the mixed dataset show an increase in the number

of retrievals and the length of generated responses compared to those trained on either dataset

alone, achieving higher scores on the test set, with improvements of up to 10.9% in average CEM

performance. Additionally, models trained solely on the 2Wiki dataset demonstrate superior training

rewards but inferior average performance across three datasets compared to those trained on the

HotpotQA dataset. This may be attributed to the relatively low diversity within the 2Wiki dataset,

potentially leading to overfitting during RL training. These findings demonstrate that the diversity

of training datasets significantly affects both training efficacy and generalizability, underscoring the

importance of data diversity.

MethodHotpotQA 2Wiki Bamboogle

Avg (CEM)

EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1 EM CEM F1

HotpotQA 53.8 59.2 67.2 46.7 54.3 54.7 44.0 50.4 55.1 54.6

2Wiki 46.0 50.5 58.7 45.0 47.5 48.2 31.2 32.8 39.4 43.6

Mixture 58.0 65.4 71.9 55.4 63.6 63.7 45.6 52.8 57.7 60.6

Table 7: Performance comparison of the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model trained on different datasets.

10

Page 11:

Figure 5: The log of reward, response length, and retrieval numbers for the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model

trained on different datasets.

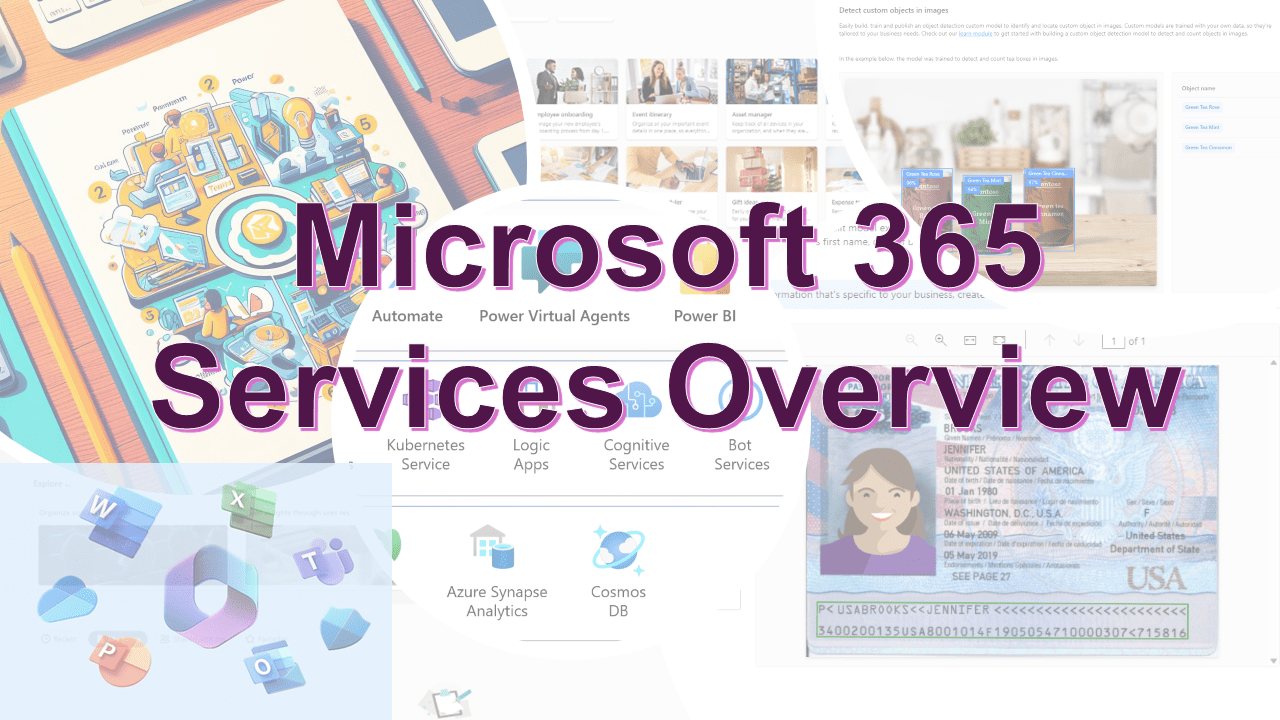

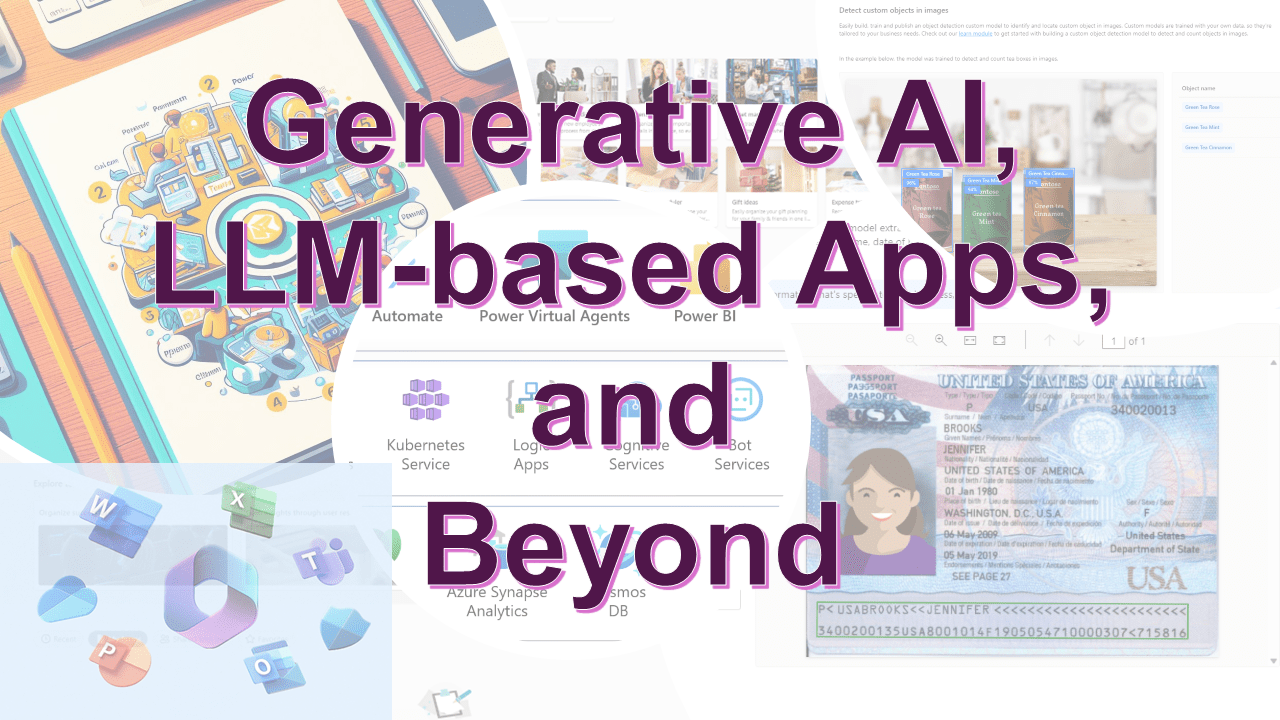

Bamboogle01020304050607080Accuracy / Percentile (%)62.4

52.8

50.456.0

22.4

17.649.648.8

27.233.6

23.227.2

24.0Qwen-2.5-7B-RL-Online (Ours)

Qwen-2.5-7B-RL-Local (Ours)

Llama-3.1-8B-RL-Local (Ours)

Search-o1 (QwQ-32B-Preview)

Marco-o1 (Qwen2-7B)

Skywork-o1 (Llama3.1-8B)

ReART eR (GPT-4o-mini)

CR-Planer (GPT-4o-mini)

IRCoT (GPT-4o-mini)

Self-Ask (GPT-4o-mini)

Iter_RetGen (GPT-4o-mini)

Standard RAG (GPT-4o-mini)

Native Generation (GPT-4o-mini)

Figure 6: Preference comparison of our models that utilize local search and online search and the

baselines on the Bamboogle dataset. Search-o1 utilizes online search, and all other baselines employ

local search.

4.4 Generalization to Online Search

In consideration of training speed and cost, we implement a local dense embedding-based retrieval

system using Wikipedia as the external retrieval environment. To evaluate the model’s generalization

capabilities beyond this knowledge scope, we test its performance on the newly proposed Bamboogle

task using an online search scenario, which is not encountered during the RL training. Specifically,

when retrieval is required, we employ the Google API to perform online searches, obtaining relevant

web pages. Due to the extensive length of these pages, we first summarize them using GPT-4o-mini

before integrating the summaries into the reasoning model. As illustrated in Figure 6, our model

demonstrates an 18.2% improvement over the local retrieval system with the same Qwen-2.5-7B-Base

backbone. Additionally, it achieves an 11.4% performance increase compared to Search-o1, which

utilizes a larger 32B backbone model with the same online search. This indicates our model’s

adaptability to online search scenarios and shows that R1-Searcher enables the model to retrieve

information during reasoning rather than merely memorizing response formats.

11

Page 12:

5 Case Study

5.1 RL v.s. SFT

Compared to SFT, RL is better at invoking external retrieval for querying when it doesn’t know

how to answer by itself. However, SFT is prone to being influenced by internal knowledge and

directly uses the incorrect internal knowledge to answer, ultimately resulting in wrong answers to the

questions. We have presented a detailed comparison as shown in Table 8.

5.2 Qwen v.s. Llama

As shown in Table 9, after RL, the Qwen-2.5-7B-Base model more effectively decomposes complex

questions than the Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct model. It refines reasoning by breaking down multi-step

problems into subproblems and sequentially retrieving relevant information, thereby increasing the

likelihood of retrieving pertinent documents and enhancing accuracy.

Question:

When did the last king from Britain’s House of Hanover die?

Answer:

20 June 1837

Response (RL) (True) :

To solve this question, I need to find out when the last king from Britain’s House of Hanover died.

Step 1: Identify the name of the last king from the House of Hanover. Step 2: Determine the date of the

last king’s death.

**Step 1: Identify the name of the last king from the House of Hanover.**

I’ll use a search query to find out:

<|begin_of_query|> last king from Britain’s House of Hanover<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

From the search results, I can see that the last British monarch who reigned in Hanover was William IV .

**Step 2: Determine the date of the last king’s death.**

I’ll use a search query to find out when William IV died:

<|begin_of_query|> William IV of Hanover death date<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

From the search results, I can see that William IV died on 20 June 1837.

Therefore, the last king from Britain’s House of Hanover died on 20 June 1837.</think>

<answer> 20 June 1837 </answer>

Response (SFT) (False) :

To answer this question, I need to recall the British monarchs who belonged to the House of Hanover

and identify the last one. The House of Hanover includes kings like George I, George II, and George III.

I need to find out when George III, the last Hanoverian king, passed away.

George III ruled from 1760 to 1820. After his death, the throne passed to his son, George IV , who was

from the House of Hanover’s successor, the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

I will verify the date of George III’s death to provide the correct answer. <|begin_of_query|> George III

death date<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

George III died on 29 January 1820. This confirms that he was the last king from Britain’s House of

Hanover, and there was no Hanoverian king after him.

The answer is 29 January 1820. </think> <answer> 29 January 1820 </answer>

Table 8: Case study from the Bamboogle dataset comparing Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct models trained

with RL and SFT.

12

Page 13:

Question:

Who was president of the United States in the year that Citibank was founded?

Answer:

james madison

Response (Qwen-2.5-7B-Base) (True) :

To solve this question, I need to find out who the president of the United States was in the year that

Citibank was founded and then identify that president.

Step 1: Determine the year Citibank was founded. I’ll use a search query to find out:

<|begin_of_query|> Citibank founding year<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

From the search results, I can see that Citibank was founded in 1812.

Step 2: Identify the president of the United States in 1812. I’ll use a search query to find out:

<|begin_of_query|> president of the United States in 1812<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

The search results mention that James Madison was the President of the United States in 1812.

Therefore, the president of the United States in the year that Citibank was founded was James Madi-

son.</think>

<answer> James Madison </answer>

Response (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct) (True) :

Given the information, I don’t have specific knowledge about the president of the United States in the

year Citibank was founded. I will perform a search to find the required information. The query to search

for is "<|begin_of_query|> president of united states citibank founded<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

Based on the search results, I found that Citibank was founded in 1812, and I couldn’t find specific

information about the president of the United States in that year. I will perform another search to

find the required information. The query to search for is "<|begin_of_query|> president united states

1812<|end_of_query|>

<|begin_of_documents|>

. . .

<|end_of_documents|>

Based on the search results, I found that the president of the United States in 1812 was James Madi-

son.</think>

<answer>James Madison</answer>

Table 9: Case study from the Bamboogle dataset comparing Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct and Llama-3.1-

8B-Instruct models trained with RL.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we propose R1-Searcher, a novel framework integrating RAG with RL. This framework

employs a two-stage outcome-supervised RL approach, which enables the model to learn to invoke

an external search engine to acquire relevant knowledge during the reasoning process through a

meticulously designed reward mechanism. The proposed method relies solely on RL, allowing the

model to learn autonomously through exploration without requiring any instruction fine-tuning for

cold start. It demonstrates the ability to generalize from in-domain training datasets to out-of-domain

test datasets while seamlessly switching to online search to obtain up-to-date information. Moreover,

R1-Searcher is applicable to both base models and instruction-tuned models. Extensive experiments

conducted on multiple datasets show that R1-Searcher outperforms traditional RAG methods and

other reasoning approaches. Additionally, we analyze the training process from various aspects,

including training methods, data, and reward designing.

7 Future Work

In future work, we aim to refine our training methodology in two key areas. First, we will explore

more sophisticated data curricula, as we have observed that the distribution and difficulty of training

13

Page 14:

data significantly influence the learning process. So far, we have only employed simple data mixing,

and a more structured approach may further enhance performance. Second, we plan to scale up our

model beyond the current 7B configuration, investigating larger models (e.g., 32B) to better assess

the effectiveness of our approach.

References

[1]Aaron Jaech, Adam Kalai, Adam Lerer, Adam Richardson, Ahmed El-Kishky, Aiden Low,

Alec Helyar, Aleksander Madry, Alex Beutel, Alex Carney, Alex Iftimie, Alex Karpenko,

Alex Tachard Passos, Alexander Neitz, Alexander Prokofiev, Alexander Wei, Allison Tam,

Ally Bennett, Ananya Kumar, Andre Saraiva, Andrea Vallone, Andrew Duberstein, Andrew

Kondrich, Andrey Mishchenko, Andy Applebaum, Angela Jiang, Ashvin Nair, Barret Zoph,

Behrooz Ghorbani, Ben Rossen, Benjamin Sokolowsky, Boaz Barak, Bob McGrew, Borys

Minaiev, Botao Hao, Bowen Baker, Brandon Houghton, Brandon McKinzie, Brydon Eastman,

Camillo Lugaresi, Cary Bassin, Cary Hudson, Chak Ming Li, Charles de Bourcy, Chelsea V oss,

Chen Shen, Chong Zhang, Chris Koch, Chris Orsinger, Christopher Hesse, Claudia Fischer,

Clive Chan, Dan Roberts, Daniel Kappler, Daniel Levy, Daniel Selsam, David Dohan, David

Farhi, David Mely, David Robinson, Dimitris Tsipras, Doug Li, Dragos Oprica, Eben Freeman,

Eddie Zhang, Edmund Wong, Elizabeth Proehl, Enoch Cheung, Eric Mitchell, Eric Wallace,

Erik Ritter, Evan Mays, Fan Wang, Felipe Petroski Such, Filippo Raso, Florencia Leoni, Foivos

Tsimpourlas, Francis Song, Fred von Lohmann, Freddie Sulit, Geoff Salmon, Giambattista

Parascandolo, Gildas Chabot, Grace Zhao, Greg Brockman, Guillaume Leclerc, Hadi Salman,

Haiming Bao, Hao Sheng, Hart Andrin, Hessam Bagherinezhad, Hongyu Ren, Hunter Lightman,

Hyung Won Chung, Ian Kivlichan, Ian O’Connell, Ian Osband, Ignasi Clavera Gilaberte, and

Ilge Akkaya. Openai o1 system card. CoRR , abs/2412.16720, 2024.

[2]DeepSeek-AI, Daya Guo, Dejian Yang, Haowei Zhang, Junxiao Song, Ruoyu Zhang, Runxin

Xu, Qihao Zhu, Shirong Ma, Peiyi Wang, Xiao Bi, Xiaokang Zhang, Xingkai Yu, Yu Wu,

Z. F. Wu, Zhibin Gou, Zhihong Shao, Zhuoshu Li, Ziyi Gao, Aixin Liu, Bing Xue, Bingxuan

Wang, Bochao Wu, Bei Feng, Chengda Lu, Chenggang Zhao, Chengqi Deng, Chenyu Zhang,

Chong Ruan, Damai Dai, Deli Chen, Dongjie Ji, Erhang Li, Fangyun Lin, Fucong Dai, Fuli

Luo, Guangbo Hao, Guanting Chen, Guowei Li, H. Zhang, Han Bao, Hanwei Xu, Haocheng

Wang, Honghui Ding, Huajian Xin, Huazuo Gao, Hui Qu, Hui Li, Jianzhong Guo, Jiashi Li,

Jiawei Wang, Jingchang Chen, Jingyang Yuan, Junjie Qiu, Junlong Li, J. L. Cai, Jiaqi Ni, Jian

Liang, Jin Chen, Kai Dong, Kai Hu, Kaige Gao, Kang Guan, Kexin Huang, Kuai Yu, Lean

Wang, Lecong Zhang, Liang Zhao, Litong Wang, Liyue Zhang, Lei Xu, Leyi Xia, Mingchuan

Zhang, Minghua Zhang, Minghui Tang, Meng Li, Miaojun Wang, Mingming Li, Ning Tian,

Panpan Huang, Peng Zhang, Qiancheng Wang, Qinyu Chen, Qiushi Du, Ruiqi Ge, Ruisong

Zhang, Ruizhe Pan, Runji Wang, R. J. Chen, R. L. Jin, Ruyi Chen, Shanghao Lu, Shangyan

Zhou, Shanhuang Chen, Shengfeng Ye, Shiyu Wang, Shuiping Yu, Shunfeng Zhou, Shuting

Pan, and S. S. Li. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement

learning. CoRR , abs/2501.12948, 2025.

[3]Kimi Team, Angang Du, Bofei Gao, Bowei Xing, Changjiu Jiang, Cheng Chen, Cheng Li,

Chenjun Xiao, Chenzhuang Du, Chonghua Liao, Chuning Tang, Congcong Wang, Dehao Zhang,

Enming Yuan, Enzhe Lu, Fengxiang Tang, Flood Sung, Guangda Wei, Guokun Lai, Haiqing

Guo, Han Zhu, Hao Ding, Hao Hu, Hao Yang, Hao Zhang, Haotian Yao, Haotian Zhao, Haoyu

Lu, Haoze Li, Haozhen Yu, Hongcheng Gao, Huabin Zheng, Huan Yuan, Jia Chen, Jianhang

Guo, Jianlin Su, Jianzhou Wang, Jie Zhao, Jin Zhang, Jingyuan Liu, Junjie Yan, Junyan Wu,

Lidong Shi, Ling Ye, Longhui Yu, Mengnan Dong, Neo Zhang, Ningchen Ma, Qiwei Pan,

Qucheng Gong, Shaowei Liu, Shengling Ma, Shupeng Wei, Sihan Cao, Siying Huang, Tao

Jiang, Weihao Gao, Weimin Xiong, Weiran He, Weixiao Huang, Wenhao Wu, Wenyang He,

Xianghui Wei, Xianqing Jia, Xingzhe Wu, Xinran Xu, Xinxing Zu, Xinyu Zhou, Xuehai Pan,

Y . Charles, Yang Li, Yangyang Hu, Yangyang Liu, Yanru Chen, Yejie Wang, Yibo Liu, Yidao

Qin, Yifeng Liu, Ying Yang, Yiping Bao, Yulun Du, Yuxin Wu, Yuzhi Wang, Zaida Zhou,

Zhaoji Wang, Zhaowei Li, Zhen Zhu, Zheng Zhang, Zhexu Wang, Zhilin Yang, Zhiqi Huang,

Zihao Huang, Ziyao Xu, and Zonghan Yang. Kimi k1.5: Scaling reinforcement learning with

llms. CoRR , abs/2501.12599, 2025.

14

Page 15:

[4]Zhipeng Chen, Yingqian Min, Beichen Zhang, Jie Chen, Jinhao Jiang, Daixuan Cheng,

Wayne Xin Zhao, Zheng Liu, Xu Miao, Yang Lu, Lei Fang, Zhongyuan Wang, and Ji-Rong

Wen. An empirical study on eliciting and improving r1-like reasoning models, 2025.

[5]Zhilin Yang, Peng Qi, Saizheng Zhang, Yoshua Bengio, William Cohen, Ruslan Salakhutdinov,

and Christopher D Manning. Hotpotqa: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question

answering. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language

Processing , pages 2369–2380, 2018.

[6]Xanh Ho, Anh-Khoa Duong Nguyen, Saku Sugawara, and Akiko Aizawa. Constructing a

multi-hop qa dataset for comprehensive evaluation of reasoning steps. In Proceedings of the

28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics , pages 6609–6625, 2020.

[7]Shuting Wang, Jiejun Tan, Zhicheng Dou, and Ji-Rong Wen. Omnieval: An omnidirectional

and automatic rag evaluation benchmark in financial domain, 2025.

[8]Joohyun Lee and Minji Roh. Multi-reranker: Maximizing performance of retrieval-augmented

generation in the financerag challenge, 2024.

[9]Ofir Press, Muru Zhang, Sewon Min, Ludwig Schmidt, Noah A Smith, and Mike Lewis.

Measuring and narrowing the compositionality gap in language models. In Findings of the

Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 , pages 5687–5711, 2023.

[10] Jie He, Nan Hu, Wanqiu Long, Jiaoyan Chen, and Jeff Z. Pan. Mintqa: A multi-hop question

answering benchmark for evaluating llms on new and tail knowledge, 2025.

[11] Jinhao Jiang, Jiayi Chen, Junyi Li, Ruiyang Ren, Shijie Wang, Wayne Xin Zhao, Yang Song, and

Tao Zhang. Rag-star: Enhancing deliberative reasoning with retrieval augmented verification

and refinement. CoRR , abs/2412.12881, 2024.

[12] Yunfan Gao, Yun Xiong, Xinyu Gao, Kangxiang Jia, Jinliu Pan, Yuxi Bi, Yi Dai, Jiawei Sun,

Meng Wang, and Haofen Wang. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A

survey, 2024.

[13] Wenqi Fan, Yujuan Ding, Liangbo Ning, Shijie Wang, Hengyun Li, Dawei Yin, Tat-Seng Chua,

and Qing Li. A survey on rag meeting llms: Towards retrieval-augmented large language

models. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery

and Data Mining , KDD ’24, page 6491–6501, New York, NY , USA, 2024. Association for

Computing Machinery.

[14] Jinhao Jiang, Jiayi Chen, Junyi Li, Ruiyang Ren, Shijie Wang, Wayne Xin Zhao, Yang Song, and

Tao Zhang. Rag-star: Enhancing deliberative reasoning with retrieval augmented verification

and refinement. CoRR , abs/2412.12881, 2024.

[15] Akari Asai, Zeqiu Wu, Yizhong Wang, Avirup Sil, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi. Self-rag: Learn-

ing to retrieve, generate, and critique through self-reflection. In The Twelfth International

Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, May 7-11, 2024 . Open-

Review.net, 2024.

[16] Fengwei Teng, Zhaoyang Yu, Quan Shi, Jiayi Zhang, Chenglin Wu, and Yuyu Luo. Atom of

thoughts for markov llm test-time scaling, 2025.

[17] Liang Wang, Haonan Chen, Nan Yang, Xiaolong Huang, Zhicheng Dou, and Furu Wei. Chain-

of-retrieval augmented generation. CoRR , abs/2501.14342, 2025.

[18] Tianzhe Chu, Yuexiang Zhai, Jihan Yang, Shengbang Tong, Saining Xie, Dale Schuurmans,

Quoc V . Le, Sergey Levine, and Yi Ma. Sft memorizes, rl generalizes: A comparative study of

foundation model post-training, 2025.

[19] Xingxuan Li, Weiwen Xu, Ruochen Zhao, Fangkai Jiao, Shafiq Joty, and Lidong Bing. Can we

further elicit reasoning in llms? critic-guided planning with retrieval-augmentation for solving

challenging tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.01428 , 2024.

[20] Jian Hu. Reinforce++: A simple and efficient approach for aligning large language models,

2025.

[21] Qwen, :, An Yang, Baosong Yang, Beichen Zhang, Binyuan Hui, Bo Zheng, Bowen Yu,

Chengyuan Li, Dayiheng Liu, Fei Huang, Haoran Wei, Huan Lin, Jian Yang, Jianhong Tu,

Jianwei Zhang, Jianxin Yang, Jiaxi Yang, Jingren Zhou, Junyang Lin, Kai Dang, Keming Lu,

Keqin Bao, Kexin Yang, Le Yu, Mei Li, Mingfeng Xue, Pei Zhang, Qin Zhu, Rui Men, Runji

15

Page 16:

Lin, Tianhao Li, Tianyi Tang, Tingyu Xia, Xingzhang Ren, Xuancheng Ren, Yang Fan, Yang

Su, Yichang Zhang, Yu Wan, Yuqiong Liu, Zeyu Cui, Zhenru Zhang, and Zihan Qiu. Qwen2.5

technical report, 2025.

[22] Harsh Trivedi, Niranjan Balasubramanian, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. Musique:

Multihop questions via single-hop question composition. Transactions of the Association for

Computational Linguistics , 10:539–554, 2022.

[23] Zhongxiang Sun, Qipeng Wang, Weijie Yu, Xiaoxue Zang, Kai Zheng, Jun Xu, Xiao Zhang,

Song Yang, and Han Li. Rearter: Retrieval-augmented reasoning with trustworthy process

rewarding, 2025.

[24] Jaehyung Kim, Jaehyun Nam, Sangwoo Mo, Jongjin Park, Sang-Woo Lee, Minjoon Seo, Jung-

Woo Ha, and Jinwoo Shin. Sure: Summarizing retrievals using answer candidates for open-

domain QA of LLMs. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations ,

2024.

[25] Weijia Shi, Sewon Min, Michihiro Yasunaga, Minjoon Seo, Rich James, Mike Lewis, Luke

Zettlemoyer, and Wen-tau Yih. Replug: Retrieval-augmented black-box language models. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2301.12652 , 2023.

[26] Huiqiang Jiang, Qianhui Wu, Xufang Luo, Dongsheng Li, Chin-Yew Lin, Yuqing Yang, and

Lili Qiu. Longllmlingua: Accelerating and enhancing llms in long context scenarios via prompt

compression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06839 , 2023.

[27] Fangyuan Xu, Weijia Shi, and Eunsol Choi. RECOMP: Improving retrieval-augmented LMs

with context compression and selective augmentation. In The Twelfth International Conference

on Learning Representations , 2024.

[28] Yucheng Li, Bo Dong, Frank Guerin, and Chenghua Lin. Compressing context to enhance

inference efficiency of large language models. In Houda Bouamor, Juan Pino, and Kalika

Bali, editors, Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language

Processing , pages 6342–6353, Singapore, December 2023. Association for Computational

Linguistics.

[29] Yile Wang, Peng Li, Maosong Sun, and Yang Liu. Self-knowledge guided retrieval augmentation

for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05002 , 2023.

[30] Ofir Press, Muru Zhang, Sewon Min, Ludwig Schmidt, Noah A Smith, and Mike Lewis.

Measuring and narrowing the compositionality gap in language models. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2210.03350 , 2022.

[31] Zhihong Shao, Yeyun Gong, Yelong Shen, Minlie Huang, Nan Duan, and Weizhu Chen.

Enhancing retrieval-augmented large language models with iterative retrieval-generation synergy.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.15294 , 2023.

[32] Harsh Trivedi, Niranjan Balasubramanian, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. Interleaving

retrieval with chain-of-thought reasoning for knowledge-intensive multi-step questions. In

Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics

(Volume 1: Long Papers) , pages 10014–10037, 2023.

[33] Yu Zhao, Huifeng Yin, Bo Zeng, Hao Wang, Tianqi Shi, Chenyang Lyu, Longyue Wang, Weihua

Luo, and Kaifu Zhang. Marco-o1: Towards open reasoning models for open-ended solutions.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.14405 , 2024.

[34] Skywork o1 Team. Skywork-o1 open series. https://huggingface.co/Skywork , Novem-

ber 2024.

[35] Jiajie Jin, Yutao Zhu, Xinyu Yang, Chenghao Zhang, and Zhicheng Dou. Flashrag: A modular

toolkit for efficient retrieval-augmented generation research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13576 ,

2024.

[36] Fabio Petroni, Aleksandra Piktus, Angela Fan, Patrick S. H. Lewis, Majid Yazdani, Nicola De

Cao, James Thorne, Yacine Jernite, Vladimir Karpukhin, Jean Maillard, Vassilis Plachouras, Tim

Rocktäschel, and Sebastian Riedel. KILT: a benchmark for knowledge intensive language tasks.

In Kristina Toutanova, Anna Rumshisky, Luke Zettlemoyer, Dilek Hakkani-Tür, Iz Beltagy,

Steven Bethard, Ryan Cotterell, Tanmoy Chakraborty, and Yichao Zhou, editors, Proceedings

of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational

Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2021, Online, June 6-11, 2021 , pages

2523–2544. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

16

Page 17:

[37] Samyam Rajbhandari, Jeff Rasley, Olatunji Ruwase, and Yuxiong He. Zero: Memory optimiza-

tions toward training trillion parameter models, 2020.

[38] Zhihong Shao, Peiyi Wang, Qihao Zhu, Runxin Xu, Junxiao Song, Xiao Bi, Haowei Zhang,

Mingchuan Zhang, Y . K. Li, Y . Wu, and Daya Guo. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of

mathematical reasoning in open language models, 2024.

17