Authors: Qijiong Liu, Jieming Zhu, Lu Fan, Kun Wang, Hengchang Hu, Wei Guo, Yong Liu, Xiao-Ming Wu

Paper Content:

Page 1:

Benchmarking LLMs in Recommendation Tasks:

A Comparative Evaluation with Conventional Recommenders

Qijiong Liu

The HK PolyU

Hong Kong SAR

liu@qijiong.workJieming Zhu

Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab

Hong Kong SAR

jiemingzhu@ieee.orgLu Fan

The HK PolyU

Hong Kong SAR

cslfan@comp.polyu.edu.hk

Kun Wang

Nanyang Technology University

Singapore

wk520529@mail.ustc.edu.cnHengchang Hu

National University of Singapore

Singapore

hengchang.hu@u.nus.eduWei Guo

Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab

Singapore

guowei67@huawei.com

Yong Liu

Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab

Singapore

liu.yong6@huawei.comXiao-Ming Wu∗

The HK PolyU

Hong Kong SAR

xiao-ming.wu@polyu.edu.hk

ABSTRACT

In recent years, integrating large language models (LLMs) into rec-

ommender systems has created new opportunities for improving

recommendation quality. However, a comprehensive benchmark is

needed to thoroughly evaluate and compare the recommendation

capabilities of LLMs with traditional recommender systems. In this

paper, we introduce RecBench , which systematically investigates

various item representation forms (including unique identifier, text,

semantic embedding, and semantic identifier) and evaluates two

primary recommendation tasks, i.e., click-through rate prediction

(CTR) and sequential recommendation (SeqRec). Our extensive ex-

periments cover up to 17 large models and are conducted across

five diverse datasets from fashion, news, video, books, and music

domains. Our findings indicate that LLM-based recommenders out-

perform conventional recommenders, achieving up to a 5% AUC

improvement in the CTR scenario and up to a 170% NDCG@10

improvement in the SeqRec scenario. However, these substantial

performance gains come at the expense of significantly reduced in-

ference efficiency, rendering the LLM-as-RS paradigm impractical

for real-time recommendation environments. We aim for our find-

ings to inspire future research, including recommendation-specific

model acceleration methods. We will release our code, data, config-

urations, and platform1to enable other researchers to reproduce

and build upon our experimental results.

∗Xiao-Ming Wu is the corresponding author.

1https://recbench.github.io

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than the

author(s) must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or

republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission

and/or a fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

©2025 Copyright held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights licensed to ACM.

ACM ISBN 978-x-xxxx-xxxx-x/YY/MM

https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnnCCS CONCEPTS

•Information systems →Recommender systems ;Language

models ;•General and reference →Evaluation .

KEYWORDS

Recommender systems, Large language models, Benchmark

ACM Reference Format:

Qijiong Liu, Jieming Zhu, Lu Fan, Kun Wang, Hengchang Hu, Wei Guo, Yong

Liu, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2025. Benchmarking LLMs in Recommendation

Tasks: A Comparative Evaluation with Conventional Recommenders. In

Proceedings of ACM Conference (Conference’17). ACM, New York, NY, USA,

11 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn

1 INTRODUCTION

Recommender systems are essential for providing personalized in-

formation to internet users. The design of these systems typically

involves balancing multiple objectives, including fairness, diversity,

and interpretability. However, in industrial applications, accuracy

and efficiency are the two most crucial metrics. Accuracy forms

the foundation of user experience, greatly influencing user satisfac-

tion and engagement. Meanwhile, efficiency is crucial for system

deployment, ensuring that recommendations are generated and

delivered promptly.

In recent years, the integration of large language models (LLMs)

into recommender systems (denoted as LLM+RS ) has garnered

significant attention from both academia and industry. These inte-

grations can be broadly categorized into two paradigms [ 2,4,70,77]:

LLM-for-RS andLLM-as-RS .LLM-for-RS retains traditional deep

learning-based recommender models (DLRMs) and enhances them

through advanced feature engineering or feature encoding tech-

niques using LLMs [ 34,67]. This paradigm functions as a plug-in

module, seamlessly integrating with existing recommender systems.

It is easy to deploy, maintains high efficiency, and often improves

recommendation accuracy without significant overhead, making it

well-suited for industrial scenarios. LLM-as-RS , in contrast, directlyarXiv:2503.05493v1 [cs.IR] 7 Mar 2025

Page 2:

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA Trovato and Tobin, et al.

ITEM

ITEMITEM

ITEMA user has browsed the following items:

A user has browsed the following items: ,

, ,

, ?.

Will the user be interested in

.

Next, the user will interact with:YES LLM as RS Pair-wise Recommendation (Click-through Rate Prediction)

List-wise Recommendation (Sequential Recommendation / Generative Retrieval)DLR M

DLR M LLM as RSITEMITEM

ITEMITEMITEM

ITEMITEMITEM

ITEMITEM

ITEM

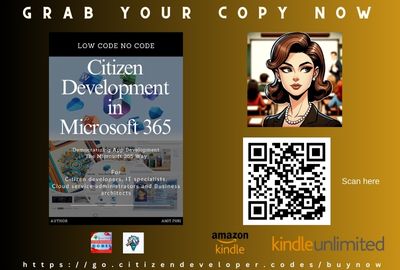

Figure 1: Illustration of DLRM and LLM recommender in two scenarios. Each

ITEM represents a placeholder that can be filled

with various item representations, including unique identifier ,text,semantic embedding orsemantic identifier .

using LLMs as recommenders to generate recommendations. Stud-

ies have shown the superiority of this paradigm in recommendation

accuracy in specific contexts, such as cold-start scenarios [ 1], and

tasks requiring natural language understanding and generation, like

interpretable and interactive recommendations [ 16,41,63]. Despite

its potential, the extremely low inference efficiency of large models

poses challenges for high-throughput recommendation tasks. Nev-

ertheless, the LLM-as-RS paradigm is transforming the traditional

recommendation pipeline designs.

Several benchmarks have been proposed for the LLM-as-RS

paradigm, including LLMRec [ 32], PromptRec [ 71], and others [ 21,

33,76]. However, as illustrated in Table 1, these benchmarks i)

provide only a limited evaluation of recommendation scenarios,

often focusing on a single scenario. Furthermore, ii)their coverage

of item representation forms for alignment within LLMs is narrow,

typically restricted to conventional unique identifier ortextformats.

In addition, iii)the number of traditional models, large-scale models,

and datasets evaluated remains relatively small, resulting in an

incomplete and fragmented performance landscape in this domain.

To address this gap, we propose the RecBench platform, which

offers a comprehensive evaluation of the LLM-as-RS paradigm.

Firstly, we investigate various item representation and alignment

methods between recommendation scenarios and LLMs, including

unique identifier ,text, and semantic embedding , and semantic iden-

tifier , to understand their impact on recommendation performance.

Secondly, the benchmark covers two main recommendation tasks:

click-through rate (CTR) prediction and sequential recommendation

(SeqRec) , corresponding to pair-wise and list-wise recommenda-

tion scenarios, respectively. Thirdly, our study evaluates up to

17LLMs, encompassing general-purpose models (e.g., Llama [ 7])

and recommendation-specific models (e.g., RecGPT [ 44]). This ex-

tensive evaluation supports multidimensional comparisons across

models of different sizes (e.g., OPT baseand OPT large), from various

institutions (e.g., Llama and Qwen), and different versions from the

same institution (e.g., Llama-1 7Band Llama-2 7B).Fourthly, the ex-

periments are conducted across fiverecommendation datasets from

different domains –including fashion (HM [ 30]), news (MIND [ 69]),

video (MicroLens [ 45]), books (Goodreads [ 58]), and music (Ama-

zon CDs [ 15])–to avoid reliance on a single platform and ensure

balanced comparisons. Fifthly, we assess both recommendation

accuracy and efficiency , providing a holistic comparison between

conventional DLRMs and the LLM-as-RS paradigm. Our evalua-

tion includes both zero-shot and fine-tuning schemes. The zero-shotevaluation explores the inherent recommendation knowledge and

reasoning capabilities of LLMs, while the fine-tuning evaluation

assesses their adaptability and learning ability in new scenarios.

To summarize, our RecBench benchmark offers an in-depth

assessment of the LLM-as-RS paradigm and yields several key in-

sights: Firstly , although LLM-based recommenders demonstrate

substantial performance improvements in various scenarios, their

efficiency limitations impede practical deployment. Future research

should focus on developing inference acceleration techniques for

LLMs in recommendations. Secondly , conventional DLRMs en-

hanced with LLM support (i.e., the LLM-for-RS paradigm, Group

Cin Figure 2) can achieve up to 95% of the performance of stan-

dalone LLM recommenders while operating much faster. Therefore,

improving the integration of LLM capabilities into conventional

DLRMs represents a promising research direction. We hope our

established, reusable, and standardized RecBench to lower the eval-

uation barrier and accelerate the development of new models in

the recommendation community.

2 PRELIMINARIES AND RELATED WORK

In this section, we provide an overview of the key techniques for

integrating LLMs with recommender systems. We begin by describ-

ing various forms of item representation, which is the foundation

of the recommender systems. Given that existing LLM-as-RS ap-

proaches employ different representations across diverse tasks, we

present an abstract framework to illustrate both LLM-based rec-

ommenders and DLRMs at a conceptual level. Subsequently, we

review representative works within each subarea to highlight cur-

rent advancements. Finally, we compare proposed RecBench with

existing benchmarks to underscore its unique contributions.

2.1 Item Representations

Item representation is a critical component of recommender sys-

tems. Since the introduction of deep learning in this field, the most

prevalent approach [ 13,60,61] has been to use item unique identi-

fier. These identifiers initially lack intrinsic meaning, and their

corresponding vectors are randomly initialized before training.

Through user–item interactions, these vectors progressively learn

and encode collaborative signals, which are used to infer unknown

interactions.

With advancements in computational power and the advent of

the big data era, item content–such as product images and news

headlines–has increasingly been utilized for item representation.

Page 3:

RecBench Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

Table 1: Comparison of RecBench with existing benchmarks within the LLM-as-RS paradigm. The notation “–” indicates that,

despite its claims, LLMRec does not practically support list-wise recommendation.

Benchmark Zhang et al. OpenP5 LLMRec PromptRec Jiang et al. RSBench RecBench

Year 2021 2024 2023c 2024b 2024 2024d (ours)

Scale#DLRM 2 9 13 4 6 0 10

#LLM 4 2 7 4 7 1 17

#Dataset 1 3 1 3 4 3 5

SchemeZero-shot ✓× ✓ ✓ × ✓ ✓

Fine-tune ✓ ✓ ✓ × ✓× ✓

Item

Representationunique identifier × ✓ ✓ × × × ✓

text ✓× ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

semantic embedding × × × × × × ✓

semantic identifier × × × × × × ✓

ScenarioPair-wise × ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

List-wise ✓ ✓ –× × × ✓

MetricQuality ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

Efficiency × × × × × × ✓

Incorporating content features significantly enhances the robust-

ness of item representations, making their quality independent of

the number of interactions. As long as content is available, any

item can be represented equally. By employing pooling operations,

convolutional neural networks [ 26], attention networks [ 57], or

other shallow modules, the item textcan be easily fused and served

as a unified item representation for the recommendation model.

In recent years, the pretrained language models (PLMs), learned

from general semantic corpus and possessing powerful semantic

understanding abilities, are widely used to extract textual represen-

tation in various domains. In the recommendation domain, these

open-source language models are also integrated with the recom-

mendation model and served as the end-to-end item encoder, fine-

tuned with the recommendation tasks. The semantic embedding has

been proven to be more effective than text, as the former introduce

rich general semantics into the recommendation model [ 35,42,68].

Additionally, a new form of item representation: semantic iden-

tifier , is introduced in the most recent years. Based on semantic

embeddings obtained from the LLMs, discrete encoding techniques

like RQ-VAE [ 27,36] are used to map all items into unique, share-

able identifier combinations. Items with similar content will have

longer common subsequences. The use of semantic identifier not

only efficiently compresses the item vocabulary, but also maintains

solid semantic connections during training [38, 40].

The emergence and advantages of the semantic identifier have

reshaped sequential recommendation methods, also known as gen-

erative retrieval [ 48,50,62,64]. They provide new input forms

and alignment strategies between LLMs and recommender sys-

tems, paving the way for advancements in the LLM-as-RS para-

digm [40, 78].2.2 Evaluation Scenarios

As LLMs demonstrate significant reasoning capabilities across vari-

ous domains [ 23,25,66], the recommendation community has be-

gun to explore their direct application to recommendation tasks [ 6,

31]. This LLM-as-RS paradigm completely abandons conventional

DLRMs, aiming to leverage the robust semantic understanding and

deep Transformer architectures of LLMs to capture item features

and model user preferences, ultimately generating recommenda-

tion results. To better understand how LLMs function within this

paradigm, we consider two common recommendation evaluation

scenarios, illustrated in Figure 1:

Pair-wise Recommendation , also known as straightforward

recommendation [ 72], corresponds to the traditional Click-Through

Rate (CTR) prediction task [ 13,60]. The input consists of a user-

item pair, and the LLM is expected to output a recommendation

score for this pair (e.g., the predicted likelihood that the user will

click on the item).

List-wise Recommendation typically corresponds to sequen-

tial recommendation tasks [ 22,54]. The input comprises a sequence

of items with positive feedback from a user, and the LLM is expected

to predict the next item that the user is likely to engage with. In

contrast to DLRMs that use structured feature inputs, the LLM-as-

RSparadigm requires concatenating inputs in natural language and

guiding the LLM to generate the final results.

2.3 LLMs as Recommender Systems

The progression of LLM-as-RS can be divided into three stages:

Stage One: Utilizing LLMs for Recommendations without

Fine-tuning. In the initial stage, researchers explored whether

general-purpose LLMs possess inherent recommendation abilities

without any fine-tuning–a zero-shot setting. Experimental results

Page 4:

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA Trovato and Tobin, et al.

indicated that while these methods [ 6,31,76] did not outperform

conventional recommendation models, they were more effective

than purely random recommendations, demonstrating a limited but

noteworthy ability for LLMs to make recommendations. Represen-

tative works in this stage include LMasRS [ 76] based on BERT [ 24]

and studies utilizing ChatGPT [ 46]. Since LLMs at this point could

only process textual information, textwas the sole form of item rep-

resentation, serving as a bridge between LLMs and recommender

systems across domains.

Stage Two: Fine-Tuning LLMs for Recommendation. In the

second stage, researchers leveraged the deep reasoning abilities

of LLMs by conducting supervised training on specific datasets

to adapt them to recommendation scenarios. For example, Uni-

CTR [9] and Recformer [28] continued to use semantic text as the

medium for aligning recommender systems with LLMs, perform-

ing multi-scenario learning in pair-wise recommendation settings.

Additionally, LLMs began to learn from non-textual signals dur-

ing this phase. Models like P5 [ 10,72] and VIP5 [ 11] used item

unique identifier for multi-task training on Amazon datasets [ 15],

covering tasks such as score prediction, next-item prediction, and

review generation. Furthermore, LLaRA [ 29] and LLM4IDRec [ 5]

fine-tuned LLMs in sequential recommendation scenarios, enabling

them to handle user behavior sequences more effectively.

Stage Three: Integration of Semantic Identifiers with LLMs.

In the most recent stage, researchers combined semantic identifier

with LLMs to enhance recommendation performance [ 17]. For in-

stance, LC-Rec [ 78] extended the multi-task learning paradigm

of P5 but replaced item representations with semantic identifiers,

achieving breakthrough results. STORE [ 40] innovatively proposed

a unified framework that integrates discrete semantic encoding with

generative recommendation, further advancing the capabilities of

LLM-based recommender systems in multiple recommendation

scenarios.

2.4 Comparison with Previous Benchmarks

Table 1 summarizes the existing benchmarks within the LLM-as-RS

paradigm. Zhang et al .pioneered the use of language models for

sequential recommendation, evaluating BERT’s recabilities in both

zero-shot and fine-tuning scenarios on the MovieLens dataset [ 14].

This work marked the inception of research into using LLMs directly

as recommender systems.

OpenP5 [ 72] builds upon the P5 [ 10] method to evaluate multiple

recommendation scenarios alongside conventional methods but uti-

lizes only unique identifiers for item representation. PromptRec [ 71]

focuses on cold-start scenarios, comparing LLMs and conventional

DLRMs using solely semantic text for zero-shot recommendation,

thereby highlighting the advantages of LLMs in content understand-

ing. Jiang et al .[21] employs multidimensional evaluation metrics

but fine-tunes LLMs exclusively using semantic text. RSBench [ 33]

primarily optimizes for conversational recommendation scenarios

but uses only a single LLM and lacks comparisons with traditional

recommendation models. LLMRec [ 32] imitates P5 by training LLMs

through multitask learning and employs both unique identifiers and

semantic text as item representations. However, LLMRec does not

incorporate semantic identifiers into item representations. More

importantly, it conducts experiments only on the Amazon Beautydataset [ 15], limiting its generalizability and credibility as a bench-

mark.

OurRecBench provides a comprehensive evaluation of the rec-

ommendation abilities of seventeen LLMs across five datasets,

encompassing both zero-shot and fine-tuning paradigms. Based on

four forms of item representation and assessed in two recommen-

dation scenarios, our benchmark uniquely evaluates the efficiency

of recommendation models, aligning with the principles of Green

AI [52] in the era of large models.

3 PROPOSED BENCHMARK: RECBENCH

In this section, we will provide a comprehensive description on our

benchmarking approaches in two recommendation scenarios.

3.1 Pair-wise Recommendation

Pair-wise recommendation estimates the probability ˆ𝑦𝑢,𝑡that a

user 𝑢interacts with (e.g., clicks on) an item 𝑡. Models are typically

trained with binary cross-entropy loss:

L=−∑︁

(𝑢,𝑡)∈D�

𝑦𝑢,𝑡logˆ𝑦𝑢,𝑡+(1−𝑦𝑢,𝑡)log(1−ˆ𝑦𝑢,𝑡)�

,(1)

whereDis the set of all user–item interactions. As illustrated in

Figure 1, we use user behavior sequence as the user-side feature.

Group A: Deep CTR models with unique identifier .For

these models, each item embedding tis randomly initialized. A

user is represented by averaging the embeddings of items in their

behavior sequence:

u=1

𝑁𝑢𝑁𝑢∑︁

𝑖=1t𝑢𝑖, (2)

where 𝑁𝑢is the sequence length. The CTR model Φpredicts the

click probability as:

ˆ𝑦𝑢,𝑡=Φ(u,t). (3)

The models to be benchmarked include DNN, PNN [ 49], DCN [ 60],

DCNv2 [ 60], DeepFM [ 13], MaskNet [ 65], FinalMLP [ 43], AutoInt [ 53],

and GDCN [59].

Group B: Deep CTR models with text.These models learn

item representations from textual features:

t=1

𝑁𝑡𝑁𝑡∑︁

𝑖=1w𝑡𝑖, (4)

where 𝑁𝑡is the text sequence length, and w𝑡denotes the item

text sequence embeddings. Models include DNN text, DCNv2 text,

AutoInt text, and GDCN text.

Group C: Deep CTR models with semantic embedding .Here,

item embeddings are initialized with pretrained semantic represen-

tations:

t=𝑔(w𝑡), (5)

where 𝑔represents a large language model. We benchmark DNN emb,

DCNv2 emb, AutoInt emb, and GDCN embmodels.

Group D: LLM with unique identifier .Following P5 [ 10], we

treat item unique identifiers as special tokens and fine-tune LLMs

for recommendation. The classification logits 𝑙yesand𝑙nofor the

YESandNOtokens are obtained from the final token. After softmax

Page 5:

RecBench Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

Unique Identi�er <Item I D: 834> <Item I D: 208>

<Item I D: 023> <Item I D: 679>

Love Story Baby

Stay FortnightText

Love Story

Fortnight0.12 0.39

0.15 0.440.81 0.27

0.73 0.20… …

… …0.38 0.66

0.30 0.59Baby

StaySemantic Embedding

Love Story

FortnightBaby

Stay3 4

3 45 2 1 1

5 2 2 5Semantic Identi�er Group A Group D

DeepFMtext Group B

DeepFMemb Group CN/A

N/AN/A

N/ADeepFM SASRec Group G Group I

P5-Llama-3

Group E

Llama-3P5-BERT

SID-Llama-3 Group J Group H Pair-wise Recommend ation

i.e., Click-through Rate Prediction Item Representation List-wise Recommend ation

i.e., Sequential Recommendation

Traditional RS Traditional RS LLM as RS LLM as RS v.s. v.s. SID-SASRec SID-Llama-3N/AN/A Group E

Group F

Figure 2: (Left) Various forms of item representations. (Right) Benchmarking groups and their representative methods.

normalization over these two tokens, the click probability is:

ˆ𝑦𝑢,𝑡=𝑒𝑙yes

𝑒𝑙yes+𝑒𝑙no. (6)

Benchmarks inlcude P5-BERT base, P5-OPT 350M , P5-OPT 1B, and P5-

Llama-3 7B.

Group E: LLM with text.In this group, items are represented

solely by their textual features, without adding extra tokens. Owing

to their natural language understanding, these LLMs are evalu-

ated in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. Benchmarks in-

clude general-purpose models such as GPT-3.5 [ 46], the LLaMA se-

ries [ 7,55,56], Qwen [ 73], OPT [ 75], Phi [ 19], Mistral [ 20], GLM [ 12],

DeepSeek-Qwen-2 [ 3], as well as recommendation-specific models

like P5 [10] and RecGPT [44].

Group F: LLM with semantic identifier .Here, we replace

the single unique identifier with multiple semantic identifiers per

item. We benchmark SID-BERT baseand SID-OPT 350M, which use

BERT baseand OPT 350M as LLM backbone, respectively.

3.2 List-wise Recommendation

List-wise recommendation predicts the next item 𝑡𝑢𝑥that a user

𝑢will interact with, given their historical behavior sequence s𝑢=�

𝑠𝑢𝑖 𝑥−1

𝑖=1. The model is trained using categorical cross-entropy loss:

L=−∑︁

𝑢∈Ulogexp�𝑓(s𝑢, 𝑡𝑢𝑥)�

Í

𝑡′∈Texp(𝑓(s𝑢, 𝑡′)), (7)

whereUdenotes the set of users, 𝑡𝑢𝑥is the true next item, Tis the

candidate set, and 𝑓(s𝑢, 𝑡′)computes the compatibility score.

Group G: SeqRec models with unique identifier .We bench-

mark a typical sequential recommendation model, SASRec [ 22],

which uses item identifiers. The prediction score is defined as:

𝑓(s𝑢, 𝑡𝑢𝑖)=v𝑇

𝑢𝑖h𝑢𝑖−1, (8)

where h𝑢𝑖−1summarizes the user history up to 𝑖−1, and v𝑢𝑖denotes

the latent classification vector for item 𝑡𝑢𝑖.Group H: SeqRec models with semantic identifier .In this

group, we extend the next-token prediction task (as in Group G) by

representing each item with multiple semantic identifiers instead

of a single unique identifier. This formulation decomposes an item

into a sequence of tokens, where each valid token combination

corresponds to a specific item. We benchmark the SID-SASRec

model, which use SASRec model as backbone.

During inference, we employ an autoregressive decoding strat-

egy using beam search. At each decoding step, the model predicts

a set of candidate tokens and maintains the top K partial sequences

(beams) based on their cumulative scores. However, since the item

representation is structured as a path in a pre-constructed semantic

identifier tree, standard beam search can produce token sequences

that do not correspond to any valid item.

To overcome this limitation, we introduce a conditional beam

search (CBS) technique. In our CBS approach, the semantic iden-

tifier tree organizes valid token sequences as paths from the root

to a leaf node. At every decoding step, the candidate tokens for

each beam are filtered to retain only those that extend the cur-

rent partial sequence to a valid prefix in the semantic identifier

tree. This restriction ensures that each beam can eventually form

a complete, valid item identifier. Only the tokens that lead to a

leaf node–representing a complete and valid semantic identifier

sequence–are allowed to contribute a positive prediction logit. We

use -CBS to denote the model inference with CBS.

Group I: LLMs with unique identifier .We extend the LLM-

based framework to list-wise recommendation by incorporating

item unique identifiers directly into the input prompt. The model is

fine-tuned on the next-item prediction task by minimizing the cat-

egorical cross-entropy loss introduced in Group G. Benchmarks in-

clude P5-BERT base, P5-Qwen-2 0.5B, P5-Qwen-2 1.5B, and P5-OPT 1B.

Group J: LLMs with semantic identifier .Compared with

Group I, we replace the item unique identifier with the seman-

tic identifier in the input prompt. The model is fine-tuned using

the categorical cross-entropy loss introduced in Group G. Condi-

tional beam search is employed to ensure that the decoded semantic

Page 6:

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA Trovato and Tobin, et al.

Table 2: Datasets statistics. “Micro.” and “Good.” represent

the MicroLens and Goodreads dataset, respectively.

Dataset H&M MIND Micro. Good. CDs

Type Fashion News Video Book Music

Text Attribute desc title title name name

Pair-wise

Test set#Sample 20,000 20,006 20,000 20,009 20,003

#Item 26,270 3,088 15,166 26,664 36,765

#User 5,000 1,514 5,000 1,736 4,930

Pair-wise

Finetune set#Sample 100,000 100,000 100,000 100,005 100,003

#Item 60,589 17,356 19,111 74,112 113,671

#User 25,000 8,706 25,000 8,604 24,618

List-wise

Test set#Seq 5,000 5,000 5,000 5,000 5,000

#Item 15,889 10,634 12,273 38,868 19,684

List-wise

Finetune set#Seq 40,000 40,000 40,000 40,000 40,000

#Item 35,344 24,451 18,841 136,296 95,409

identifier sequence maps to a valid item. Benchmarks include SID-

BERT baseand SID-Llama-3 7B.

4 EXPERIMENTAL SETUP

4.1 Datasets

To avoid reliance on a single platform, we conduct all the exper-

iments on five datasets from distinct domains and institutions:

H&M for fashion recommendation, MIND for news recommenda-

tion, MicroLens for video recommendation, Goodreads for book

recommendation, and CDs for music recommendation. Moreover,

since the training and testing data sizes of the original datasets

vary significantly, the comprehensive evaluation scores of the final

models could be influenced by these discrepancies. To mitigate

this issue, we perform uniform preprocessing on all datasets to

obtain approximately similar dataset sizes. The specific details of

the datasets are summarized in Table 2.

4.2 Evaluation Metrics

Following common practice [ 8,37,39,74], we evaluate recommen-

dation performance using widely adopted metrics, including rank-

ing metrics such as GAUC ,nDCG , and MRR , as well as matching

metrics like F1andRecall . However, due to space limitations, we

present only the GAUC metric for pair-wise recommendation tasks

andnDCG@10 for list-wise recommendation scenarios. The full

evaluation results will available on our webpage.

Moreover, we use the latency (ms) metric to evaluate the model’s

inference efficiency, calculated as the average time per inference

over 1,000 runs on a single CPU device.

4.3 Implementation Details

Data Pre-processing. For datasets lacking user behavior sequences

(i.e., HM, CDs, Goodreads, and MicroLens), we construct these se-

quences by arranging each user’s positive interactions in chronolog-

ical order. In the pair-wise recommendation scenario, for datasets

without provided negative samples (i.e., MicroLens and HM), weperform negative sampling for each user with a negative ratio of 2.

Additionally, we truncate user behavior sequences to a maximum

length of 20 to ensure consistency across datasets. For deep CTR

models, i) we utilize the nltk package to tokenize the text data and

subsequently retain only those tokens present in the GloVe vocab-

ulary [ 47] under the textsettings, and we did not use pretrained

GloVe vectors during training; ii) we use Llama-1 7Bmodel to ex-

tract the pretrained item embeddings under the semantic embedding

settings.

Semantic Identifier Generation. We employ the pipeline proposed

by TIGER [ 50] to generate semantic identifier . First, we use an

LLM, i.e., SentenceBERT [ 51], to extract embeddings for each item

content. Then, we perform discretization training using the RQ-

VAE [ 27] model on these embeddings. Following common prac-

tice [ 40,50,64], we utilize a 4-layer codebook, with each layer

having a size of 256. The representation space of this codebook

approximately reaches 4 billion.

Identifier Vocabulary. Regardless of whether we use unique iden-

tifier orsemantic identifier , we construct new identifier vocabularies

for the LLM. Specifically, the vocabulary size 𝑉matches the number

of items when using unique identifier , or𝑉=256×4=1,024when

using semantic identifier . We initialize a randomly generated em-

bedding matrix Eid∈R𝑉×𝑑, where 𝑑is the embedding dimension

of the current LLM.

Model Fine-tuning. We employ the low-rank adaptation (LoRA)

technique [ 18] for parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large language

models. For the pair-wise recommendation scenario, LoRA is config-

ured with a rank of 32 and an alpha of 128, whereas for the list-wise

recommendation scenario, these parameters are set to (128, 128).

The learning rate is fixed at 1×10−4for LLM-based models and

1×10−3for other models. In addition, we set the batch size to

5,000 for all deep CTR models, 64 for models with fewer than 7B

parameters, and 16 for models with 7B parameters.

5 PAIR-WISE RECOMMENDATION: FINDINGS

In this section, we present a comprehensive analysis of experimental

results evaluating the recommendation abilities of LLMs in pair-

wise recommendation scenarios.

5.1 Can LLMs Recommend in Zero-Shot Mode?

Most LLMs exhibit limited zero-shot recommendation

abilities; however, models pretrained on data containing

implicit recommendation signals, such as Mistral [ 20],

GLM [12], and Qwen-2 [73], perform significantly better.

Table 3 presents the performance of various LLMs on pair-wise

recommendation scenario across multiple recommendation datasets.

We report the AUC metric, where values closer to 0.5 indicate

performance near random recommendations. Our findings reveal

that most LLMs–from small-scale BERT [ 24] models to large-scale

Llama [ 7,55,56] variants–struggle with general recommendation

tasks. Although item representations are provided in textform that

Page 7:

RecBench Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

Table 3: LLM zero-shot performance in the pair-wise recom-

mendation scenario. We display AUC metric in this table.

Latency is the averaged inference time per sample.

Recommender MIND Micro. Good. CDs H&M Overall Latency

BERT base 0.4963 0.4992 0.4958 0.5059 0.5204 0.5035 53.26ms

OPT 350M 0.5490 0.4773 0.5015 0.5093 0.4555 0.4985 332.34ms

OPT 1B 0.5338 0.5236 0.5042 0.4994 0.5650 0.5252 1.14s

Llama-1 7B 0.4583 0.4572 0.4994 0.4995 0.4035 0.4636 3.17s

Llama-2 7B 0.4945 0.4877 0.5273 0.5191 0.4519 0.4961 6.20s

Llama-3 8B 0.4904 0.5577 0.5191 0.5136 0.5454 0.5252 6.80s

Llama-3.1 8B 0.5002 0.5403 0.5271 0.5088 0.5462 0.5245 6.58s

Mistral 7B 0.6300 0.6579 0.5718 0.5230 0.7166 0.6199 7.68s

GLM-4 9B 0.6304 0.6647 0.5671 0.5213 0.7319 0.6231 9.69s

Qwen-2 0.5B 0.4868 0.5717 0.5148 0.5043 0.6287 0.5413 543.73

Qwen-2 1.5B 0.5411 0.6072 0.5264 0.5174 0.6615 0.5707 1.42s

Qwen-2 7B 0.5862 0.6640 0.5494 0.5256 0.7124 0.6075 6.15s

DS-Qwen-2 7B0.5127 0.5631 0.5165 0.5146 0.5994 0.5413 7.52s

Phi-2 3B 0.4851 0.5078 0.5049 0.4991 0.5447 0.5083 2.10s

GPT-3.5 0.5057 0.5110 0.5122 0.5046 0.5801 0.5227 -

RecGPT 7B 0.5078 0.4703 0.5083 0.5019 0.4875 0.4952 7.16s

P5Beauty 0.4911 0.5017 0.5027 0.5447 0.4845 0.5049 74.11ms

the LLMs can process, these models appear to have difficulty ex-

tracting user interests from behavior sequences and assessing the

relevance between user interests and candidate items.

Moreover, specialized recommendation models such as P5 [ 10]

and RecGPT [ 44] also underperformed in our evaluations. P5, being

an ID-based LLM recommender, effectively captures item semantics

only on fine-tuned datasets (e.g., Beauty [ 15]), while RecGPT, a

text-based recommendation model, suffers from similar limitations

due to dataset-specific fine-tuning. This suggests both models lack

strong generalization and zero-shot inference capabilities.

Notably, the Mistral [ 20], GLM [ 12], and Qwen-2 [ 73] models

demonstrated comparatively robust CTR prediction performance,

with the recommendation effectiveness of Qwen-2 showing a posi-

tive correlation with model size. We hypothesize that these models

may have been exposed to a broader mix of web content–including

user interactions, reviews, and implicit recommendation signals–

which could contribute to their enhanced generalization to recom-

mendation tasks.

5.2 Can Fine-tuning Enhance LLM

Recommendation Performance?

Fine-tuning significantly enhances the recommendation

accuracy of LLMs. For instance, Llama-3 7Byields improve-

ments of up to 43% after fine-tuning.

Subsequently, we perform instruction tuning on various LLMs

across each dataset, aligning their capabilities with recommenda-

tion tasks through click-through rate prediction. Based on Table 3

and Table 4, our experiments indicate that such fine-tuning yields

a relative improvement in recommendation accuracy ranging from22% to 43%, underscoring the importance of domain-specific align-

ment.

Notably, Llama-3 7Boutperformed Mistral-2 7Bon the MicroLens

and Goodreads datasets. Although Mistral-2 ranked among the top

three in zero-shot scenarios, the overall performance of Llama-3 was

comparable to that of Mistral-2, while smaller models such as BERT

and OPT consistently lagged behind. These results highlight the

superior semantic understanding and deep reasoning capabilities

inherent in larger models.

Table 4: Comparison between fine-tuned LLM and conven-

tional DLRMs in the pair-wise recommendation scenario.

We display AUC metric in this table. Latency is the averaged

inference time per sample.

Recommender MIND Micro. Good. CDs H&M Overall Latency

DNN 0.6692 0.7421 0.5831 0.5757 0.7952 0.6731 0.43ms

PNN 0.6581 0.7359 0.5801 0.5331 0.7648 0.6544 0.51ms

DeepFM 0.6670 0.7594 0.5782 0.5681 0.7749 0.6695 0.51ms

DCN 0.6625 0.7410 0.5902 0.5780 0.7913 0.6726 0.58ms

DCNv2 0.6707 0.7578 0.5778 0.5664 0.7950 0.6735 4.43ms

MaskNet 0.6631 0.7179 0.5719 0.5532 0.7481 0.6508 3.12ms

FinalMLP 0.6649 0.7600 0.5807 0.5670 0.7858 0.6717 0.62ms

AutoInt 0.6690 0.7451 0.5879 0.5789 0.8027 0.6767 0.93ms

GDCN 0.6704 0.7571 0.5948 0.5784 0.8120 0.6825 0.69ms

DNN text 0.6867 0.7741 0.5857 0.5655 0.8475 0.6919 1.05ms

DCNv2 text 0.6802 0.7804 0.5789 0.5577 0.8560 0.6906 5.15ms

AutoInt text 0.6701 0.7761 0.5803 0.5687 0.8490 0.6888 1.41ms

GDCN text 0.6783 0.7842 0.5796 0.5641 0.8555 0.6923 1.21ms

DNN emb 0.7154 0.8141 0.5997 0.5848 0.8717 0.7171 1.32ms

DCNv2 emb 0.7167 0.8061 0.5999 0.5944 0.8626 0.7159 4.81ms

AutoInt emb 0.7081 0.8099 0.6015 0.5560 0.8594 0.7070 1.71ms

GDCN emb 0.7093 0.7997 0.5943 0.5828 0.8565 0.7085 1.63ms

P5-BERT base 0.5507 0.5850 0.5038 0.5162 0.5402 0.5392 38.01ms

P5-OPT base 0.6330 0.5099 0.5031 0.4989 0.4939 0.5278 255.70ms

P5-OPT large 0.6512 0.6984 0.5110 0.5281 0.6177 0.6013 950.89ms

P5-Llama-3 7B0.6697 0.7457 0.5780 0.5688 0.7260 0.6576 6.35s

BERT base 0.7175 0.8066 0.5148 0.5789 0.8635 0.6962 53.26ms

OPT 1B 0.7346 0.8016 0.5889 0.5850 0.5121 0.6444 1.14s

Llama-3 7B 0.7345 0.8328 0.6826 0.6268 0.8771 0.7508 6.80s

Mistral-2 7B 0.7353 0.8295 0.6680 0.6754 0.8810 0.7578 7.68s

SID-BERT base 0.5704 0.5860 0.4914 0.5042 0.5401 0.5384 36.40ms

SID-OPT base 0.5987 0.4989 0.5004 0.4977 0.4957 0.5183 286.56ms

5.3 Performance Comparison: LLMs vs.

Conventional Deep CTR Models

Large-scale LLMs (e.g., Llama, Mistral) achieve over a 5%

improvement in recommendation accuracy compared to

the best conventional recommender (DNN emb) using se-

mantic embedding . However, these gains come with signif-

icant latency; the best conventional recommender retains

95% of the performance while being 5,800 times faster.

Page 8:

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA Trovato and Tobin, et al.

Table 5: Comparison between LLM recommenders and con-

ventional DLRMs in the list-wise recommendation scenario.

We display NDCG@10 metric in this table. Latency is the

averaged inference time per sample. “ -CBS” denote models

applying conditional beam search technique (described in

Sec 3.2) during inference.

Recommender MIND Micro. Good. CDs H&M Overall Latency

SASRec 3L 0.0090 0.0000 0.0165 0.0016 0.0209 0.0096 23.30ms

SASRec 6L 0.0097 0.0006 0.0224 0.0012 0.0297 0.0127 38.43ms

SASRec 12L 0.0241 0.0297 0.0548 0.1041 0.1235 0.0672 51.77ms

SASRec 24L 0.0119 0.0312 0.0601 0.1267 0.1191 0.0698 103.41ms

BERT base 0.0430 0.1867 0.0557 0.1198 0.1075 0.1025 41.54ms

QWen-2 0.5B 0.0549 0.0201 0.0322 0.0128 0.0234 0.0287 556.95ms

QWen-2 1.5B 0.0506 0.0254 0.0316 0.0015 0.0217 0.0262 1.12s

Llama-3 7B 0.0550 0.0178 0.0134 0.0072 0.0353 0.0257 28.06s

SID-SASRec 3L 0.0266 0.0028 0.0029 0.0000 0.0084 0.0081 36.12ms

SID-SASRec 3L-CBS 0.0849 0.0123 0.0127 0.0007 0.0422 0.0306 66.67ms

SID-SASRec 6L 0.0225 0.0047 0.0038 0.0140 0.0097 0.0109 59.08ms

SID-SASRec 6L-CBS 0.0647 0.0179 0.0141 0.0331 0.0406 0.0341 90.41ms

SID-SASRec 12L 0.0201 0.0044 0.0039 0.0136 0.0165 0.0117 1.31s

SID-SASRec 12L-CBS 0.0695 0.0234 0.0140 0.0324 0.0598 0.0398 1.34s

SID-BERT base 0.0654 0.0022 0.0025 0.3539 0.0467 0.0941 1.83s

SID-BERT base-CBS 0.1682 0.1195 0.0059 0.4616 0.1834 0.1877 1.90s

SID-Llama-3 7B 0.0456 0.0255 0.0221 0.2443 0.0337 0.0742 167.25s

SID-Llama-3 7B-CBS 0.1677 0.0827 0.0508 0.3898 0.1125 0.1607 177.54s

Table 4 compares recommendation performance using various

item representation forms for both conventional recommenders

(i.e., DLRM) and LLM-based approaches. The key findings are as

follows:

Firstly, even without textual modalities, conventional unique

identifier -based CTR models outperform the zero-shot LLM-based

recommenders (Table 3), highlighting the importance of interac-

tion data. Moreover, fine-tuned unique identifier -based LLMs still

lag behind, likely because they struggle to capture explicit fea-

ture interactions. Secondly, incorporating textual data into CTR

models yields significant gains. We did not use pretrained word em-

beddings, as the item-side text itself effectively learns robust item

relationships. Thirdly, initializing item representations with em-

beddings from Llama-1 for semantic embedding -based CTR models

introduces high-quality semantic information, outperforming both

prior methods and small text-based LLMs (e.g., BERT, OPT) due to

Llama’s superior semantic quality and deeper network architecture.

Fourthly, text-based LLMs using large models like Llama-3 and

Mistral-2 outperform all baselines, demonstrating their disruptive

potential in recommendation tasks. Fifthly, conversely, fine-tuning

semantic identifier -based LLMs yields poor performance in CTR

scenarios, likely due to smaller models’ limited ability to learn dis-

crete semantic information. Sixthly, in terms of efficiency, semantic

embedding -based CTR models within the LLM-for-RS paradigm

offer the best cost-effectiveness with minimal modifications to tradi-

tional architectures, making this approach one of the most practical

in industry.6 LIST-WISE RECOMMENDATION: FINDINGS

In this section, we present the results from the list-wise recommen-

dation scenario. Notably, sequential recommenders [ 22,50] typi-

cally rely on next-item prediction to map user histories to specific

items, which is incompatible with using textas the item represen-

tation. Consequently, we focus on evaluating two forms: unique

identifier and semantic identifier . Since LLMs do not inherently

recognize these unseen tokens, they exhibit no zero-shot recom-

mendation abilities and require fine-tuning.

6.1 Unique ID vs. Semantic ID

Overall, semantic identifier has shown to be a more effective

representation than unique identifier , whether integrated

with LLMs or traditional recommenders, highlighting the

value of incorporating item content knowledge into se-

quential recommenders.

Based on Table 5, which evaluates the recommendation abilities

of LLMs and conventional DLRMs in the list-wise recommendation

scenario, we can make the following observations:

Firstly, within the SASRec series, performance generally im-

proves with an increasing number of transformer layers, reflecting

the scaling behavior of conventional sequential recommenders. No-

tably, SID-SASRec outperforms standard SASRec when using a

smaller number of layers. This suggests that semantic identifier –by

decomposing item representations into logically and hierarchically

structured tokens–enables shallower networks to better capture

user interests. However, as the number of layers increases, the ad-

vantage of semantic identifier diminishes, likely because deeper

architectures in SASRec can more effectively learn user sequence

patterns, even without pretrained semantic information.

Secondly, comparing the pairs (BERT base, SID-BERT base-CBS ),

and (Llama-3 7B, SID-Llama-3 7B-CBS ) pairs, we observe that LLMs

with semantic identifier consistently outperform their unique iden-

tifier counterparts, achieving improvements of up to 83%. This

underscores the efficiency and potential of the semantic identifier

representation in enhancing recommendation performance.

6.2 Performance Comparison: LLMs vs.

Conventional Sequential Recommenders

LLMs outperform traditional sequential recommenders in

accuracy using either unique identifier orsemantic identifier

representations, but their inference efficiency remains a

critical issue requiring urgent improvement.

Based on unique identifier representations, the BERT basemodel

outperforms both SASRec 12L–which shares the same network ar-

chitecture as BERT base–and the deeper SASRec 24L. Despite the

absence of textual features in item representations, this observation

suggests that language patterns acquired during pretraining bear

an abstract similarity to user interest patterns in recommender

systems, thereby facilitating effective knowledge transfer.

Page 9:

RecBench Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

Furthermore, LLM recommenders employing semantic identifier

representations exhibit markedly superior performance compared

to the SID-SASRec series. By incorporating semantic item knowl-

edge, semantic identifier enables LLMs to more effectively interpret

user sequences and capture high-quality user interests.

Additionally, models utilizing conditional beam search constraints

(the -CBS series) achieve further improvements in recommendation

performance. However, these gains come at a substantial cost in

inference efficiency; overall, LLM recommenders require nearly

1,000 times more inference time than SASRec. This significant effi-

ciency gap represents a critical challenge that should be addressed

to ensure the practical deployment of LLM recommenders.

7 CONCLUSION

In this work, we introduced the RecBench platform–a compre-

hensive benchmark designed to evaluate the LLM-as-RS paradigm

in recommender systems. By systematically investigating various

item representation forms and covering both click-through rate

prediction and sequential recommendation tasks, our study spans

diverse datasets and a wide range of models. Our evaluation reveals

that, while LLM-based recommenders–especially those leverag-

ing large-scale models—can achieve significant performance gains

across multiple recommendation scenarios, they continue to face

substantial efficiency challenges relative to conventional DLRMs.

This trade-off underscores the imperative for further research into

inference acceleration techniques, which are crucial for the practi-

cal deployment of LLM-based recommenders in high-throughput

industrial settings.

REFERENCES

[1]Keqin Bao, Jizhi Zhang, Yang Zhang, Wenjie Wang, Fuli Feng, and Xiangnan

He. 2023. Tallrec: An effective and efficient tuning framework to align large

language model with recommendation. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference

on Recommender Systems . 1007–1014.

[2]Keqin Bao, Jizhi Zhang, Yang Zhang, Wang Wenjie, Fuli Feng, and Xiangnan

He. 2023. Large language models for recommendation: Progresses and future

directions. In Proceedings of the Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on

Research and Development in Information Retrieval in the Asia Pacific Region .

306–309.

[3]Xiao Bi, Deli Chen, Guanting Chen, Shanhuang Chen, Damai Dai, Chengqi Deng,

Honghui Ding, Kai Dong, Qiushi Du, Zhe Fu, et al .2024. Deepseek llm: Scaling

open-source language models with longtermism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02954

(2024).

[4]Jin Chen, Zheng Liu, Xu Huang, Chenwang Wu, Qi Liu, Gangwei Jiang, Yuanhao

Pu, Yuxuan Lei, Xiaolong Chen, Xingmei Wang, et al .2024. When large language

models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World

Wide Web 27, 4 (2024), 42.

[5]Lei Chen, Chen Gao, Xiaoyi Du, Hengliang Luo, Depeng Jin, Yong Li, and Meng

Wang. 2024. Enhancing ID-based Recommendation with Large Language Models.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02041 (2024).

[6]Sunhao Dai, Ninglu Shao, Haiyuan Zhao, Weijie Yu, Zihua Si, Chen Xu, Zhongx-

iang Sun, Xiao Zhang, and Jun Xu. 2023. Uncovering chatgpt’s capabilities in

recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recom-

mender Systems . 1126–1132.

[7]Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad

Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan,

et al. 2024. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783 (2024).

[8]Junchen Fu, Xuri Ge, Xin Xin, Alexandros Karatzoglou, Ioannis Arapakis, Jie

Wang, and Joemon M Jose. 2024. IISAN: Efficiently adapting multimodal repre-

sentation for sequential recommendation with decoupled PEFT. In Proceedings

of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in

Information Retrieval . 687–697.

[9]Zichuan Fu, Xiangyang Li, Chuhan Wu, Yichao Wang, Kuicai Dong, Xiangyu

Zhao, Mengchen Zhao, Huifeng Guo, and Ruiming Tang. 2023. A unified frame-

work for multi-domain ctr prediction via large language models. ACM Transac-

tions on Information Systems (2023).[10] Shijie Geng, Shuchang Liu, Zuohui Fu, Yingqiang Ge, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2022.

Recommendation as language processing (rlp): A unified pretrain, personalized

prompt & predict paradigm (p5). In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on

Recommender Systems . 299–315.

[11] Shijie Geng, Juntao Tan, Shuchang Liu, Zuohui Fu, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2023.

Vip5: Towards multimodal foundation models for recommendation. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2305.14302 (2023).

[12] Team GLM, Aohan Zeng, Bin Xu, Bowen Wang, Chenhui Zhang, Da Yin, Dan

Zhang, Diego Rojas, Guanyu Feng, Hanlin Zhao, et al .2024. Chatglm: A fam-

ily of large language models from glm-130b to glm-4 all tools. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2406.12793 (2024).

[13] Huifeng Guo, Ruiming Tang, Yunming Ye, Zhenguo Li, and Xiuqiang He. 2017.

DeepFM: A Factorization-Machine based Neural Network for CTR Prediction.

InProceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial

Intelligence, IJCAI 2017, Melbourne, Australia, August 19-25, 2017 , Carles Sierra

(Ed.). ijcai.org, 1725–1731. https://doi.org/10.24963/IJCAI.2017/239

[14] F Maxwell Harper and Joseph A Konstan. 2015. The movielens datasets: History

and context. Acm transactions on interactive intelligent systems (tiis) 5, 4 (2015),

1–19.

[15] Ruining He and Julian McAuley. 2016. Ups and downs: Modeling the visual

evolution of fashion trends with one-class collaborative filtering. In proceedings

of the 25th international conference on world wide web . 507–517.

[16] Zhankui He, Zhouhang Xie, Rahul Jha, Harald Steck, Dawen Liang, Yesu Feng,

Bodhisattwa Prasad Majumder, Nathan Kallus, and Julian McAuley. 2023. Large

language models as zero-shot conversational recommenders. In Proceedings of the

32nd ACM international conference on information and knowledge management .

720–730.

[17] Minjie Hong, Yan Xia, Zehan Wang, Jieming Zhu, Ye Wang, Sihang Cai, Xi-

aoda Yang, Quanyu Dai, Zhenhua Dong, Zhimeng Zhang, et al .2025. EAGER-

LLM: Enhancing Large Language Models as Recommenders through Exogenous

Behavior-Semantic Integration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.14735 (2025).

[18] Edward J Hu, Yelong Shen, Phillip Wallis, Zeyuan Allen-Zhu, Yuanzhi Li, Shean

Wang, Lu Wang, Weizhu Chen, et al .2022. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large

language models. ICLR 1, 2 (2022), 3.

[19] Mojan Javaheripi, Sébastien Bubeck, Marah Abdin, Jyoti Aneja, Sebastien Bubeck,

Caio César Teodoro Mendes, Weizhu Chen, Allie Del Giorno, Ronen Eldan,

Sivakanth Gopi, et al .2023. Phi-2: The surprising power of small language

models. Microsoft Research Blog 1, 3 (2023), 3.

[20] Albert Q Jiang, Alexandre Sablayrolles, Arthur Mensch, Chris Bamford, De-

vendra Singh Chaplot, Diego de las Casas, Florian Bressand, Gianna Lengyel,

Guillaume Lample, Lucile Saulnier, et al .2023. Mistral 7B. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2310.06825 (2023).

[21] Chumeng Jiang, Jiayin Wang, Weizhi Ma, Charles LA Clarke, Shuai Wang, Chuhan

Wu, and Min Zhang. 2024. Beyond Utility: Evaluating LLM as Recommender.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.00331 (2024).

[22] Wang-Cheng Kang and Julian McAuley. 2018. Self-attentive sequential recom-

mendation. In 2018 IEEE international conference on data mining (ICDM) . IEEE,

197–206.

[23] Enkelejda Kasneci, Kathrin Seßler, Stefan Küchemann, Maria Bannert, Daryna

Dementieva, Frank Fischer, Urs Gasser, Georg Groh, Stephan Günnemann, Eyke

Hüllermeier, et al .2023. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges

of large language models for education. Learning and individual differences 103

(2023), 102274.

[24] Jacob Devlin Ming-Wei Chang Kenton and Lee Kristina Toutanova. 2019. Bert:

Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In

Proceedings of naacL-HLT , Vol. 1. Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2.

[25] Takeshi Kojima, Shixiang Shane Gu, Machel Reid, Yutaka Matsuo, and Yusuke

Iwasawa. 2022. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Advances in

neural information processing systems 35 (2022), 22199–22213.

[26] Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E Hinton. 2012. Imagenet classifi-

cation with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information

processing systems 25 (2012).

[27] Doyup Lee, Chiheon Kim, Saehoon Kim, Minsu Cho, and Wook-Shin Han. 2022.

Autoregressive image generation using residual quantization. In Proceedings of the

IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition . 11523–11532.

[28] Jiacheng Li, Ming Wang, Jin Li, Jinmiao Fu, Xin Shen, Jingbo Shang, and Julian

McAuley. 2023. Text is all you need: Learning language representations for

sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference

on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining . 1258–1267.

[29] Jiayi Liao, Sihang Li, Zhengyi Yang, Jiancan Wu, Yancheng Yuan, Xiang Wang,

and Xiangnan He. 2024. Llara: Large language-recommendation assistant. In

Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and

Development in Information Retrieval . 1785–1795.

[30] Carlos García Ling, ElizabethHMGroup, FridaRim, inversion, Jaime Ferrando,

Maggie, neuraloverflow, and xlsrln. 2022. H&M Personalized Fashion Recom-

mendations. https://kaggle.com/competitions/h-and-m-personalized-fashion-

recommendations. Kaggle.

Page 10:

Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA Trovato and Tobin, et al.

[31] Junling Liu, Chao Liu, Peilin Zhou, Renjie Lv, Kang Zhou, and Yan Zhang.

2023. Is chatgpt a good recommender? a preliminary study. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2304.10149 (2023).

[32] Junling Liu, Chao Liu, Peilin Zhou, Qichen Ye, Dading Chong, Kang Zhou, Yueqi

Xie, Yuwei Cao, Shoujin Wang, Chenyu You, et al .2023. Llmrec: Benchmarking

large language models on recommendation task. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12241

(2023).

[33] Jiao Liu, Zhu Sun, Shanshan Feng, and Yew-Soon Ong. 2024. Language Model

Evolutionary Algorithms for Recommender Systems: Benchmarks and Algorithm

Comparisons. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10697 (2024).

[34] Qijiong Liu, Nuo Chen, Tetsuya Sakai, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2023. A first look at

llm-powered generative news recommendation. CoRR (2023).

[35] Qijiong Liu, Nuo Chen, Tetsuya Sakai, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2024. Once: Boosting

content-based recommendation with both open-and closed-source large language

models. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search

and Data Mining . 452–461.

[36] Qijiong Liu, Xiaoyu Dong, Jiaren Xiao, Nuo Chen, Hengchang Hu, Jieming Zhu,

Chenxu Zhu, Tetsuya Sakai, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2024. Vector quantization for

recommender systems: a review and outlook. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.03110

(2024).

[37] Qijiong Liu, Lu Fan, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2025. Legommenders: A Comprehensive

Content-Based Recommendation Library with LLM Support.

[38] Qijiong Liu, Hengchang Hu, Jiahao Wu, Jieming Zhu, Min-Yen Kan, and Xiao-

Ming Wu. 2024. Discrete Semantic Tokenization for Deep CTR Prediction. In

Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2024 . 919–922.

[39] Qijiong Liu, Jieming Zhu, Quanyu Dai, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2022. Boosting deep

CTR prediction with a plug-and-play pre-trainer for news recommendation. In

Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics .

2823–2833.

[40] Qijiong Liu, Jieming Zhu, Lu Fan, Zhou Zhao, and Xiao-Ming Wu. 2024. STORE:

Streamlining Semantic Tokenization and Generative Recommendation with A

Single LLM. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.07276 (2024).

[41] Yucong Luo, Mingyue Cheng, Hao Zhang, Junyu Lu, Qi Liu, and Enhong Chen.

2023. Unlocking the potential of large language models for explainable recom-

mendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.15661 (2023).

[42] Itzik Malkiel, Oren Barkan, Avi Caciularu, Noam Razin, Ori Katz, and Noam

Koenigstein. 2020. RecoBERT: A catalog language model for text-based recom-

mendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.13292 (2020).

[43] Kelong Mao, Jieming Zhu, Liangcai Su, Guohao Cai, Yuru Li, and Zhenhua Dong.

2023. FinalMLP: an enhanced two-stream MLP model for CTR prediction. In

Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence , Vol. 37. 4552–4560.

[44] Hoang Ngo and Dat Quoc Nguyen. 2024. RecGPT: Generative Pre-training

for Text-based Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of

the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024 - Short Papers, Bangkok,

Thailand, August 11-16, 2024 , Lun-Wei Ku, Andre Martins, and Vivek Srikumar

(Eds.). Association for Computational Linguistics, 302–313. https://aclanthology.

org/2024.acl-short.29

[45] Yongxin Ni, Yu Cheng, Xiangyan Liu, Junchen Fu, Youhua Li, Xiangnan He,

Yongfeng Zhang, and Fajie Yuan. 2023. A Content-Driven Micro-Video Recom-

mendation Dataset at Scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.15379 (2023).

[46] OpenAI. 2023. GPT-3.5. https://openai.com/gpt Large language model.

[47] Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher D Manning. 2014. Glove:

Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on

empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP) . 1532–1543.

[48] Haohao Qu, Wenqi Fan, Zihuai Zhao, and Qing Li. 2024. TokenRec: Learning

to Tokenize ID for LLM-based Generative Recommendation. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2406.10450 (2024).

[49] Yanru Qu, Han Cai, Kan Ren, Weinan Zhang, Yong Yu, Ying Wen, and Jun Wang.

2016. Product-based neural networks for user response prediction. In 2016 IEEE

16th international conference on data mining (ICDM) . IEEE, 1149–1154.

[50] Shashank Rajput, Nikhil Mehta, Anima Singh, Raghunandan Hulikal Keshavan,

Trung Vu, Lukasz Heldt, Lichan Hong, Yi Tay, Vinh Tran, Jonah Samost, et al .

2023. Recommender systems with generative retrieval. Advances in Neural

Information Processing Systems 36 (2023), 10299–10315.

[51] Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych. 2019. Sentence-bert: Sentence embeddings

using siamese bert-networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.10084 (2019).

[52] Roy Schwartz, Jesse Dodge, Noah A Smith, and Oren Etzioni. 2020. Green ai.

Commun. ACM 63, 12 (2020), 54–63.

[53] Weiping Song, Chence Shi, Zhiping Xiao, Zhijian Duan, Yewen Xu, Ming Zhang,

and Jian Tang. 2019. Autoint: Automatic feature interaction learning via self-

attentive neural networks. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference

on information and knowledge management . 1161–1170.

[54] Fei Sun, Jun Liu, Jian Wu, Changhua Pei, Xiao Lin, Wenwu Ou, and Peng Jiang.

2019. BERT4Rec: Sequential recommendation with bidirectional encoder rep-

resentations from transformer. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM international

conference on information and knowledge management . 1441–1450.

[55] Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne

Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, FaisalAzhar, et al .2023. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2302.13971 (2023).

[56] Hugo Touvron, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yas-

mine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov, Soumya Batra, Prajjwal Bhargava, Shruti Bhos-

ale, et al .2023. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2307.09288 (2023).

[57] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones,

Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all

you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

[58] Mengting Wan and Julian J. McAuley. 2018. Item recommendation on mono-

tonic behavior chains. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recom-

mender Systems, RecSys 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada, October 2-7, 2018 , Sole Pera,

Michael D. Ekstrand, Xavier Amatriain, and John O’Donovan (Eds.). ACM, 86–94.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3240323.3240369

[59] Fangye Wang, Hansu Gu, Dongsheng Li, Tun Lu, Peng Zhang, and Ning Gu.

2023. Towards deeper, lighter and interpretable cross network for CTR predic-

tion. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM international conference on information and

knowledge management . 2523–2533.

[60] Ruoxi Wang, Bin Fu, Gang Fu, and Mingliang Wang. 2017. Deep & cross network

for ad click predictions. In Proceedings of the ADKDD’17 . 1–7.

[61] Ruoxi Wang, Rakesh Shivanna, Derek Cheng, Sagar Jain, Dong Lin, Lichan Hong,

and Ed Chi. 2021. Dcn v2: Improved deep & cross network and practical lessons

for web-scale learning to rank systems. In Proceedings of the web conference 2021 .

1785–1797.

[62] Wenjie Wang, Honghui Bao, Xinyu Lin, Jizhi Zhang, Yongqi Li, Fuli Feng, See-

Kiong Ng, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2024. Learnable Item Tokenization for Generative

Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on

Information and Knowledge Management . 2400–2409.

[63] Xiaolei Wang, Xinyu Tang, Wayne Xin Zhao, Jingyuan Wang, and Ji-Rong Wen.

2023. Rethinking the evaluation for conversational recommendation in the era

of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13112 (2023).

[64] Ye Wang, Jiahao Xun, Minjie Hong, Jieming Zhu, Tao Jin, Wang Lin, Haoyuan

Li, Linjun Li, Yan Xia, Zhou Zhao, et al .2024. EAGER: Two-Stream Generative

Recommender with Behavior-Semantic Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 30th

ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining . 3245–3254.

[65] Zhiqiang Wang, Qingyun She, and Junlin Zhang. 2021. Masknet: Introducing

feature-wise multiplication to CTR ranking models by instance-guided mask.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.07619 (2021).

[66] Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi,

Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al .2022. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning

in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 35

(2022), 24824–24837.

[67] Wei Wei, Xubin Ren, Jiabin Tang, Qinyong Wang, Lixin Su, Suqi Cheng, Jun-

feng Wang, Dawei Yin, and Chao Huang. 2024. Llmrec: Large language models

with graph augmentation for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM

International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining . 806–815.

[68] Chuhan Wu, Fangzhao Wu, Tao Qi, and Yongfeng Huang. 2021. Empowering

news recommendation with pre-trained language models. In Proceedings of the

44th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in informa-

tion retrieval . 1652–1656.

[69] Fangzhao Wu, Ying Qiao, Jiun-Hung Chen, Chuhan Wu, Tao Qi, Jianxun Lian,

Danyang Liu, Xing Xie, Jianfeng Gao, Winnie Wu, and Ming Zhou. 2020. MIND: A

Large-scale Dataset for News Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual

Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) . Association for

Computational Linguistics, Online. Presented at ACL 2020.

[70] Likang Wu, Zhi Zheng, Zhaopeng Qiu, Hao Wang, Hongchao Gu, Tingjia Shen,

Chuan Qin, Chen Zhu, Hengshu Zhu, Qi Liu, et al .2024. A survey on large

language models for recommendation. World Wide Web 27, 5 (2024), 60.

[71] Xuansheng Wu, Huachi Zhou, Yucheng Shi, Wenlin Yao, Xiao Huang, and Ning-

hao Liu. 2024. Could Small Language Models Serve as Recommenders? Towards

Data-centric Cold-start Recommendation. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web

Conference 2024 . 3566–3575.

[72] Shuyuan Xu, Wenyue Hua, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2024. Openp5: An open-source

platform for developing, training, and evaluating llm-based recommender sys-

tems. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research

and Development in Information Retrieval . 386–394.

[73] An Yang, Baosong Yang, Binyuan Hui, Bo Zheng, Bowen Yu, Chang Zhou, Cheng-

peng Li, Chengyuan Li, Dayiheng Liu, Fei Huang, et al .2024. Qwen2 technical

report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10671 (2024).

[74] Chiyu Zhang, Yifei Sun, Minghao Wu, Jun Chen, Jie Lei, Muhammad Abdul-

Mageed, Rong Jin, Angli Liu, Ji Zhu, Sem Park, et al .2024. EmbSum: Leveraging

the Summarization Capabilities of Large Language Models for Content-Based

Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender

Systems . 1010–1015.

[75] Susan Zhang, Stephen Roller, Naman Goyal, Mikel Artetxe, Moya Chen, Shuohui

Chen, Christopher Dewan, Mona Diab, Xian Li, Xi Victoria Lin, et al .2022. Opt:

Open pre-trained transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01068

(2022).

Page 11:

RecBench Conference’17, July 2017, Washington, DC, USA

[76] Yuhui Zhang, Hao Ding, Zeren Shui, Yifei Ma, James Zou, Anoop Deoras,

and Hao Wang. 2021. Language models as recommender systems: Evalua-

tions and limitations. In NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on I (Still) Can’t Believe It’s

Not Better . https://www.amazon.science/publications/language-models-as-

recommender-systems-evaluations-and-limitations

[77] Zihuai Zhao, Wenqi Fan, Jiatong Li, Yunqing Liu, Xiaowei Mei, Yiqi Wang, Zhen

Wen, Fei Wang, Xiangyu Zhao, Jiliang Tang, and Qing Li. 2024. RecommenderSystems in the Era of Large Language Models (LLMs). IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data

Eng. 36, 11 (2024), 6889–6907. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2024.3392335

[78] Bowen Zheng, Yupeng Hou, Hongyu Lu, Yu Chen, Wayne Xin Zhao, Ming

Chen, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2024. Adapting large language models by integrating

collaborative semantics for recommendation. In 2024 IEEE 40th International

Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) . IEEE, 1435–1448.